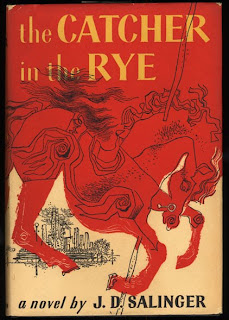

Like a lot of other people, I’ve been thinking a lot the last few weeks about J.D. Salinger, & especially about his most famous work, The Catcher in the Rye.

This, as you probably know, is the 1951 novel in which Holden Caulfield, a rich kid from Manhattan, flees the Pennsylvania prep school he’s flunked out of & heads to New York, but instead of going home spends a couple of days wandering the city, blowing money & alienating people.

I first read the book when I was in 10th grade, & again a couple of years later. I loved it, but looking back on it now, the identification that I felt with Holden, even though I shared it with millions of adolescents around the world, seems embarrassing to me. I don’t mean the kind of embarrassment one feels about some maudlin teenage poem or journal entry or yearbook inscription, nor do I mean that Catcher is a childish taste that I’ve outgrown—I do regard it as an authentic classic of American literature.

But thinking that Holden was “just like me” (or that I was just like him) seems now an overfamiliarity, an impertinence, almost an adolescent faux pas. It seems this way on two counts: social & emotional, & in both cases I’m grateful that it does.

To explain what I mean by “social,” I must indulge in autobiography: I grew up in a rural area on the other side of Pennsylvania from Holden’s prep school. I was the youngest of five kids. My Dad was a truck driver, & my Mom worked a variety of jobs to supplement his income—cashier in a book store, desk clerk in a motel, dishwasher in the cafeteria of the (public) high school I went to. Partly because of the hard work & resourcefulness of my parents, & partly because there were no seriously wealthy people in the area where I grew up—we lived next to railroad tracks, & the people who lived on The Other Side of the Tracks were no richer than we were—I never realized, as a kid, how broke we often were, & how much my parents struggled financially to provide for us.

For this reason, it never occurred to me when I read Catcher that Holden would have seen me as a poor kid, & probably wouldn’t have been comfortable with me. Indeed, thinking back on the book (I haven’t reread it) I recall Holden mentioning a roommate he had who owned shabby suitcases, & that while they liked each other, the difference in their status was an awkwardness for both of them. It never crossed my mind at the time that even this kid was probably from higher up the class ladder from me, & that in the unlikely event I ever even met Holden, it would be many times more awkward.

But the scene from Catcher that sticks most vividly in my mind all these years later is Holden’s tangle with Maurice, the pimp. After Holden’s abortive encounter with the prostitute, Maurice comes back to his room & shakes him down for five more dollars. Holden, enraged, taunts Maurice thusly (I found the passage online):

“You’re a dirty moron,” I said. “You’re a stupid chiseling moron, and in about two years you’ll be one of those scraggy guys that come up to you on the street and ask you for a dime for coffee. You’ll have snot all over your dirty overcoat, and you’ll be—”

At which point Maurice punches our hero in the stomach, knocking the wind out of him. Since the hooker has already appropriated the extra five bucks, it’s clear that Holden has touched a nerve, that Maurice punches him because he suspects his prophecy is probably accurate, & I can remember, as a teenager, enjoying Holden’s triumph.

It wasn’t until years later that it occurred to me that, socioeconomically speaking, I was ten times closer to Maurice than to Holden, & that even though I didn’t lead the life of a small-potatoes criminal it was still perfectly plausible that I could end up one of “those scraggy guys,” but that because of his class there was almost no chance that this could ever happen to Holden, no matter how he lived his life. Holden wants to catch the children before they fall off the cliff, but he doesn’t realize that he’s playing in the rye himself, & will be for the rest of his life, & that his class employs plenty of “catchers” already.

In light of this, the little snot’s prophecy somehow seemed a rather vicious response to Maurice’s pathetic chiseling. Maybe Holden (or Salinger) had a guilty pang over this as well, since at the very end of the book, when Holden is complaining that telling us his story has made him feel nostalgic for the people in it, he remarks “I think I even miss that goddam Maurice.” Well, I bet Maurice doesn’t freakin’ miss him.

The argument against all this, of course, is that class needn’t prevent identification with Holden any more than it does with, say, Hamlet (not that I’m placing the two works on the same level, of course), & that’s fair enough, on a literary level. My point here is only that I’ve walked around most of my life utterly oblivious to my class status, & in this, as I said, I regard myself as very fortunate. My parents raised me with no sense of class aspiration, & if I had actually met a kid like Holden, I probably would have just assumed that he & I could be friends, or if I had met one of the girls he dates I might have supposed that I could date her too.

Realizing that this was presumptuous of me would have been embarrassing, but aside from regret at missing out on the friendship or the date, I don’t think I would have felt any class bitterness over it. I’ve often wished I had more money, of course, but I don’t recall ever spending one second wishing that I was “high class” in the country club sense—both the obligations & amusements of that world have always seemed, from my outsider’s perspective, so tedious that I’ve always felt genuinely sorry for those who have to live in it.

Now we come to the second source of sheepishness I feel about my youthful enthusiasm for Catcher in the Rye. The novel is one of the key texts in the 20th-Century festishizing of the “young misfit.” But what makes Holden a misfit? He insists that he loathes “phonies,” while repeatedly “slinging the old bull” himself when he meets strangers, or tries to charm women, but this hardly makes him unusual among teens, nor are “phonies” really the source of the nervous breakdown toward which he’s heading.

When I read the book as a kid, the aspect of Holden’s character to which I paid the least attention—except possibly his social class—was his grief over the death of his brother Allie. What’s remarkable is how little Allie’s death figures in the commentaries I’ve read on the book (admittedly not many). This isn’t Salinger’s fault—Holden refers to Allie again & again throughout the story. One of the most moving scenes that I can recall comes when Holden, walking through the city, is overwhelmed by the feeling that he won’t make it across the streets, & mentally begs Allie to help him get across. It’s even more touching in light of the repressed, denial-oriented, stiff-upper-lip approach to bereavement that was typical, especially in Holden’s class, in the novel’s period.

But somehow all this mostly blipped past me as a teenage reader. I just thought, he’s a smart, screwed-up, special kid—like me! It never occurred to me that he was truly screwed-up, that he was acutely suffering, & for good reason. I was part of a couple of generations of teens who, thanks to Catcher & a few other cultural influences, thought that because we were bored & horny & impatient for adulthood to begin, that we were entitled—almost obligated—to be angst-ridden pains in the ass. But I had no loss in my life equivalent to Holden’s loss of Allie.

So that’s all I’m saying, I guess. For Catcher in the Rye to still be so firmly planted in my consciousness more than thirty years later, it must have been a vibrant work for me. I enjoyed Holden’s company, to a degree that I would probably never have gotten to in real-life. But, though no doubt I was an oddball kid in some ways, contrary to my earlier opinion, I was not Holden Caulfield, & neither, I’d guess, were most of the other teenage readers who thought they were. Thank God for that, too, meaning no goddam offense to Holden & all.

Monday, February 22, 2010

Subscribe to:

Post Comments (Atom)

Yow.

ReplyDeleteFor all this retro- and introspection, I guess this book did indeed affect you. (I’ll pass on your essay to my kids if they are assigned this book in school.) I remember reading Catcher In The Rye while sitting on the second floor of the Gannon library, and the act of reading such a “controversial” book in the confines of this repository of Catholicity affected me more than the book. I recall being caught up in the first few chapters, but ending the book as if I’d just watched a slightly dissatisfying movie, or took a walk downtown in the rain, but returned home with nothing really to talk about despite having done so.

I, as usual, must defer to your memory for details about the story, but there was a definite limit to my identification with the Holden character. I certainly didn’t credit this to class-consciousness, but I believe you are correct with your assessment.

Perhaps I was more elitist even then despite my own middle-class background, but I didn’t quite get how this book was supposed to be the defining voice of the teen experience. I remember wanting to be a part of it, especially due its lauded and checkered history, but failing to really find my way in.

What I did identify with was the character Heathcliff in Wuthering Heights. And, though a tough read for me, I truly loved the experience of James Joyce’s A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man. Opening this book felt like I was opening a heavy door, and the sentenced words looked like they were posted up on shelves so I would need a ladder to touch and examine them. (I said it was a tough read.) And the despairing nostalgia of John Knowle’s A Separate Peace gave me much more to consider than did Catcher in the Rye. I rarely read books twice, but these three high school assignments moved me enough to do so. And the Joyce book is calling me even now…

Thanx for the comment! Yeah, Portrait is an awesome work, as is Wuthering Heights. I haven't read A Separate Peace, though, shame of the cities. I'll put in the list. I rarely read books twice, thoughI know tthere are some people who set great store by it, & even think that you can't really say you've read a book until you've read it twice. But with some books I love I'll obsessively reread chapters or passages (like the cook's sermon to sharks in Moby-Dick). For some reason I'll reread my favorite nonfiction essays over & over a hundred times, though.

ReplyDeleteNice post M.V.

ReplyDeleteEven here in Portland, as I am typing these lines, I hear the far away sigh of a train's horn. Living close to the tracks, on either side, can make a "noisy" thing beautiful.

I listened to an old tape of an old band of mine tonight. The drummer has this song called SIlly Song. There is a line that goes "They raised you right, they raised you right but now you've gone all wrong." I'm not saying this applies to you, but something about your post reminded me of it.

Zeusthemoosebuns

I like it; thanx! The sound of the trains was always a lullaby to me; when I moved to town & the tracks were no longer nearby, I found it harder to sleep for awhile.

ReplyDelete