The other night my 10-year-old detonated a psychic land mine from my past. We were walking along when suddenly she groaned and said:

“Oh, I can’t get that song out my head.”

“What song is that, sweetie?”

“‘Chicken Fat.’”

My eyes got big. “’Chicken Fat?’” I immediately started to sing:

“

Push-ups, ev’ry morning, ten times!/Not just now and then…”

And then her eyes got big. “How you know that song?”

So I told her how. I exercised to “Chicken Fat” too, in Mrs. Robasky’s second-grade gym class, back at dear old Clark Elementary in Harborcreek, Pennsylvania in 1970. If you went to grade school, or summer camp, after 1961, there’s a chance you did too.

When we got home I consulted the inexhaustible pop-culture attic known as YouTube, and quickly

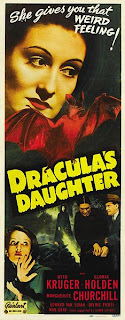

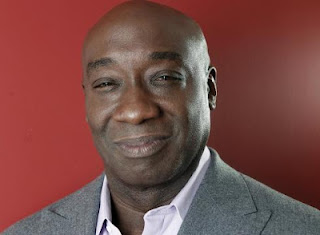

found what I was looking for: “Chicken Fat,” aka “The Youth Fitness Song,” written in ‘61 by Meredith Willson, the genius behind possibly the greatest of American musical comedies,

The Music Man, and rousingly sung by the great Robert Preston. With its catchy—indeed unshakeable—march-tempo tune, its typically witty, complex Willson lyric, and its rich orchestral and choral accompaniment, it really sounds like a discarded song from

The Music Man, but it was written for the Kennedy-era President’s Council on Physical Fitness, in an attempt to encourage daily exercise.

Nine years after its release they were still using it at my grade school. And fifty-one years after its release, according to The Kid, her 5th-grade class—taught by a woman in her twenties, early thirties at the oldest—works out to that same Boomer-era relic every morning. Not just now and then.

I was amazed. I hadn’t thought about it in decades, but I had a very clear early memory associated with that record. At lunch one day I mentioned liking it to my friend Lonnie:

“That ‘Chicken Fat’ is a good song, huh?”

Lonnie’s face darkened.

“No,” he said. “I don’t like that song.”

This perplexed me. A lively tune like that—how could anyone not like it? I was too dense to grasp why Lonnie, who was what used to be called “big-boned,” might take offense at the song. But I do now, and I was startled to learn that, in this age of official sensitivity—and with even more chubby kids around now than there were in the ‘60s and ‘70s—a contemporary teacher would consider a song with lyrics like “

…Once more on the rise/Nuts to the flabby guys/Go, you chicken fat, go away/Go you chicken fat go…” appropriate for classroom use. It’s hard to imagine Mrs. Obama approving of it, at any rate.

I’m not saying

I object to its use, mind you—the continuity of it pleases me, really. But having developed over the decades into one of the “flabby guys” that Willson and Preston say “nuts” to, I must also wonder if the overweight aren’t one of those few groups outside the umbrella of political correctness, unprotected from disparagement.

Anyway, a few days later I was listening to “Chicken Fat” again, in my office, when The Kid came in and demanded that I get up and try the exercises. So I did—grunting and wheezing, while she looked on, convulsed with hilarity, and egging me on when she thought I was slacking. I only got through seven of the ten push-ups.

After this depressing debacle, I staggered into the kitchen, sweaty and panting. The Wife, ever terrified of finding herself a single mom, glowered at me.

“If the heart attack doesn’t kill you, I will,” she promised.

But I have to admit, once my heart rate stabilized, I felt pretty invigorated. No doubt about it, if my generation had worked out with Robert Preston every morning for the last half-century, we’d be a far healthier nation.