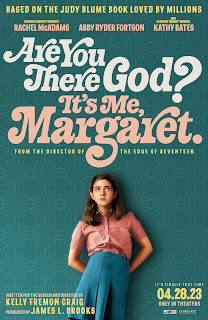

Opening this weekend:

Are You There God? It's Me, Margaret--It begins with a shot of an adolescent girl, yelling with joy. She's literally a happy camper; we're seeing the summer before our heroine Margaret turns 12, and her life changes, inside and out. She comes home from camp to learn that her family--except for her adored and adoring grandmother--is moving from New York to small town New Jersey.

She quickly falls in with a new circle of friends, all of whom are anxiously but eagerly awaiting their first periods. The child of a mixed, non-practicing Jewish-Christian marriage, Margaret is so anxious about this milestone that she nonetheless starts talking to God, politely pleading with the Almighty to let her start puberty and "be normal."

For half a century now, Judy Blume's classic, sometimes (absurdly) controversial 1970 coming-of-age novel has been almost as much a rite of passage for American girls as the social and biological shifts it dramatizes. But it's never been a movie before; reportedly Blume never liked a script until the adaptation by Kelly Fremon Craig of The Edge of Seventeen, who also directed.

Apparently Blume's instincts are good. The resulting film is a home run, sweet and low-key yet cumulatively emotional. Abby Ryder Fortson is marvelously un-histrionic and endearing as Margaret; her spot-on line readings suggest the budding phase of a wary but observant and empathetic person. Craig's script slightly fleshes out the character of Margaret's frustrated-painter Mom, and Rachel McAdams gives the character her own hints of uncertainty; Benny Safdie works well as Margaret's good-natured Dad. Kathy Bates is showcased as the jolly Grandma, a fiercely pro-Margaret partisan who is overjoyed when her granddaughter asks to be taken to Temple.

Margaret's friends are a fine ensemble, led by the amusingly impudent Elle Graham as Nancy. Frizz-haloed Aidan Wojtak-Hissong makes an impression as the lawn-mowing Moose Freed; so does Isol Young as the towering Laura Danker, who has gained a reputation on the basis of nothing more than having bloomed early. Echo Kellum seems to have stepped directly out of the '70s as the earnest newbie teacher Mr. Benedict.

This is an example of Craig's best decision: to not update the material. The movie is set in the year of the book's publication, and the production design and soundtrack invoke 1970 so vividly that it may feel like a flashback to those of us who remember it. The legion of grown-up fans of the book will likely be delighted by this fidelity.

The question, of course, is what the film will mean to audiences Margaret's age. I recently asked a mom of two daughters if girls are still embarrassed about their periods; she assured me that they are. But it's hard to say if the novel's candor on that subject is as unusual as it was in 1970.

It should be noted, of course, that menstruation, or even the issues around adolescent crushes and friendships, are far from the only themes here. A family move that you don't want but are helpless to stop, for instance, is a relatable strife for kids regardless of gender, and when Margaret looks out her bedroom window at her bustling New York neighborhood, Craig makes us feel what a loss this will be.

The story also transcends mere health class manual utility in its treatment of Margaret's religious explorations. Her gentle, personal, terror-free, open-hearted conversations with God--as in Whoever is Listening--are in healthy contrast to the stress and guilt and family conflict she experiences in connection with organized religion. The movie makes a case for a secular upbringing, even for theists.