New this week:

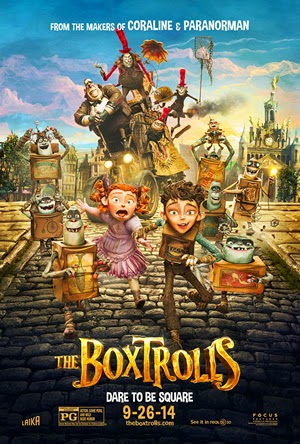

The Boxtrolls—The title characters in Laika’s new stop-motion fantasy are, um, trolls that wear boxes. They take their names from whatever’s on the sides of these packages: Fish, Shoe, Clocks, Wheels and so on.

The trolls live deep beneath Cheesbridge, a hilltop city of vaguely European and late-19th-Century character. They’re harmless to humans—they’re insectivores, and their nighttime raids on the town are aimed at its trash, which they like to repurpose. But they’ve been demonized to the Cheesebridgians by Snatcher, a scurvy exterminator, and his entourage of Dickensian henchmen.

It’s true that the Boxtrolls are raising a human boy, the “Trubshaw Baby” whose disappearance Snatcher uses to terrify the locals. But we soon learn that this is a case of foster care, not abduction.

Adapted from Alan Snow’s novel Here be Monsters! by Irina Brignull and Adam Pava and directed by Graham Annable and Anthony Stacchi, The Boxtrolls is one of the odder children’s movies to get a big release since The Pirates! Band of Misfits, another stop-motion kid flick. But Pirates! was overtly (and excellently) silly, while The Boxtrolls, though very funny, takes a more lyrically weird, fairy-tale tone. Ben Kinsgley hams it up grandly as Snatcher, leading a cast that includes Jared Harris, Nick Frost, Simon Pegg, Toni Collete, Richard Ayaode, Elle Fanning and Tracy Morgan.

The theme of the movie is pretense—Snatcher is trying, through his campaign against the Boxtrolls, to get a “White hat” making him one of the cheese-sampling city fathers. This despite his severe lactose intolerance. The trolls also react with horrified propriety whenever one of their boxes is shed, or even opened. It’s a wonderfully crazy, generous-hearted movie, though its pungency and gleeful gross-outs won’t appeal to all kids, or all adults.

The Skeleton Twins—The celebratory lip-sync. Among the tropes of comedy-drama, it’s not my favorite. You know the sort of scene I mean—characters mouth along to a song, maybe using a hairbrush or something as a microphone, sometimes solo, like Tom Cruise in Risky Business, sometimes in a group.

It’s not that I think such activities don’t happen in life, or even that I don’t think they’re fun. But they’re usually an annoyance in movies, because it seems like a lazy way to establish bonding between characters or the breaking down of a reserved character’s defenses, to get a popular tune on the soundtrack, and to kill a few minutes. It’s taking a free ride on someone else’s art.

But right in the middle of The Skeleton Twins, troubled brother Milo (Bill Hader) and troubled sister Maggie (Kristen Wiig) perform a lip-sync, to “Nothing’s Gonna Stop Us Now” by Starship. And something about the lustiness of Hader’s pantomime and the hilariously wary, reluctant acquiescence of Wiig to that appallingly effective piece of ‘80s schlock got to me. It’s a potent dramatization of how even the cheesiest pop culture can be a source of strength and a balm to the spiritually wounded.

And Maggie and Milo, differently damaged by tragic childhoods, certainly are wounded. Milo, a failed L.A. actor turned waiter who drinks too much, makes a half-hearted suicide attempt. Word of this interrupts Maggie as she’s contemplating ending it all herself. She hasn’t seen Milo in a decade, but she heads to the west coast and drags him back to their upstate New York hometown to recuperate in the house she shares with her cluelessly decent husband (Luke Wilson).

This guy wants to have a baby with her, but she’s secretly still on the pill, perhaps partly because she doesn’t want to perpetuate her family craziness, but also because she’s an unhappy serial adulteress. Milo makes himself at home, and tries to reconnect with the disgraced English teacher (Ty Burrell) with whom he had an affair back in high school.

There’s really nothing very funny about any aspect of the plot of this small film, directed by Craig Johnson from a script he wrote with Mark Heyman. The comedy arises not from the bitterly sad situation but from the resigned gallows humor with which Maggie and Milo deal with it. They’re deeply exasperating people, even to themselves, but as The Skeleton Twins progresses—partly because of that stupid lip-sync!—I started to root for them. Hader and Wiig have a rapport that does, indeed, seem fraternal.

Friday, September 26, 2014

Thursday, September 25, 2014

BUG, THEN BUNNY

Recently I recounted the turbulent construction of a Monster Scenes “Giant Insect” model kit by The Kid and myself. Well, we have obtained a second monster kit, from Dencomm, based on the Aurora Monster Scenes kits. This one is another product of mad science, a Saber Tooth Rabbit…

Friday, September 19, 2014

RUNNING/WALKING

New this week:

The Maze Runner—In the vein of The Hunger Games and Divergent, The Maze Runner is young-adult sci-fi with a body count. Based on James Dashner’s 2009 novel, it’s set in “The Glade,” a grassy, open area inhabited by adolescent boys. Their earlier lives, and how they came to The Glade are unknown to them—they’re all amnesiacs, remembering only their names.

Every now and then a freight elevator vomits up a new resident from far underground. The boys have done better at organizing themselves into a functional community than the lads in Lord of the Flies—they’ve set up an agricultural village with carefully assigned roles. The fastest, fittest and bravest of the boys serve as Maze Runners.

The Glade, you see, is enclosed by monolithic stone walls which open, during the day, to allow access to an enormous Maze. The Runners explore this by day, in hopes of mapping it and finding a way out, but are careful to get back to The Glade before the huge doors close. If they don’t, they’ll be trapped in the Maze with the Grievers, howling presences which stay out of sight during the day, but have the run of the place by night. No one, we are told, has survived a night in the Maze with the Grievers.

All this and shovel-loads more exposition is flung at the newest arrival, Thomas (Dylan O’Brien). He’s an intrepid, somewhat rebellious fellow, and he of course becomes the hot new Maze Runner, and comes face to face with the Grievers, and lives to tell the tale, and generally shakes things up in The Glade—with the result that its population is thinned. It does, however, gain a female resident, Teresa (Kaya Scodelario), who turns up in the elevator with a note declaring that she’s the last one ever.

The premise of The Maze Runner is undeniably intriguing; it stirs the imagination. And director Wes Ball stages many exciting scenes and gets vivid work out of his young cast, especially Blake Cooper, Ki Hong Lee, Aml Ameen, Thomas Brodie-Sangster and Will Poulter. What marred the film, for me, was overexplanation—in the homestretch, we get a deluge of unconvincing backstory on how this situation came to be, and the mystery and inscrutability of the boys’ plight, and its allegorical associations with life in general, are sapped of their power. The hook of the movie was negotiating the Maze itself, not learning what the Maze was for.

A Walk Among the Tombstones—When Liam Neeson tells somebody, in that soft, deep, almost apologetic tone of his, that they’re in trouble if they harm some innocent victim, it’s hard not to take his threats seriously. Thus he’s making quite a career out of playing haunted father-figure rescuers and avengers, in melodramas like Taken and Taken 2, The Grey, Non-Stop and now A Walk Among the Tombstones.

Well, it’s certainly not a Tiptoe Through the Tulips. Based on one of the Lawrence Block novels about Matthew Scudder, an ex-NYPD recovering alcoholic and unlicensed private detective, the movie is a parade of horrors, starting us off with a gruesome shoot-out before the opening credits and getting much more unsavory from there. It’s set in 1999, against the backdrop of Y2K anxiety—how quaint does that seem now?—and involves a revolting kidnapping operation run by two of the most loathsome villains (David Harbour and Adam David Thompson) to turn up in a thriller in years.

Scudder (Neeson) is hired to find these two by a swanky drug trafficker (Dan Stevens) whose wife ended up dead even though he paid the ransom. All manner of twists are unraveled, Scudder’s horrifying guilty past is revealed, and our hero also befriends a homeless teenager (Bryan “Astro” Bradley) who wants to be a detective, before the big showdown in the graveyard between good and evil—or, rather, between evil and comparatively good—arrives.

Nasty though it is, I found this Jacobean Big Apple bloodbath intense and satisfying. The script, adapted by director Scott Frank, has some creaky passages, and the strand with the teenage kid bumps up against sentimentality, though it’s well played and it allows Neeson some lighter moments. But Frank’s direction, with his measured pacing and his melancholic atmosphere reminiscent of a certain style of ‘70s urban crime thriller, is really expert.

As the movie progressed, however, I became increasingly aware that these villains were so odious that no comeuppance would be sufficient to calm my vengeful bloodlust toward them. And indeed, it wasn’t sufficient. But that’s my spiteful heart’s problem, not the movie’s.

The Maze Runner—In the vein of The Hunger Games and Divergent, The Maze Runner is young-adult sci-fi with a body count. Based on James Dashner’s 2009 novel, it’s set in “The Glade,” a grassy, open area inhabited by adolescent boys. Their earlier lives, and how they came to The Glade are unknown to them—they’re all amnesiacs, remembering only their names.

Every now and then a freight elevator vomits up a new resident from far underground. The boys have done better at organizing themselves into a functional community than the lads in Lord of the Flies—they’ve set up an agricultural village with carefully assigned roles. The fastest, fittest and bravest of the boys serve as Maze Runners.

The Glade, you see, is enclosed by monolithic stone walls which open, during the day, to allow access to an enormous Maze. The Runners explore this by day, in hopes of mapping it and finding a way out, but are careful to get back to The Glade before the huge doors close. If they don’t, they’ll be trapped in the Maze with the Grievers, howling presences which stay out of sight during the day, but have the run of the place by night. No one, we are told, has survived a night in the Maze with the Grievers.

All this and shovel-loads more exposition is flung at the newest arrival, Thomas (Dylan O’Brien). He’s an intrepid, somewhat rebellious fellow, and he of course becomes the hot new Maze Runner, and comes face to face with the Grievers, and lives to tell the tale, and generally shakes things up in The Glade—with the result that its population is thinned. It does, however, gain a female resident, Teresa (Kaya Scodelario), who turns up in the elevator with a note declaring that she’s the last one ever.

The premise of The Maze Runner is undeniably intriguing; it stirs the imagination. And director Wes Ball stages many exciting scenes and gets vivid work out of his young cast, especially Blake Cooper, Ki Hong Lee, Aml Ameen, Thomas Brodie-Sangster and Will Poulter. What marred the film, for me, was overexplanation—in the homestretch, we get a deluge of unconvincing backstory on how this situation came to be, and the mystery and inscrutability of the boys’ plight, and its allegorical associations with life in general, are sapped of their power. The hook of the movie was negotiating the Maze itself, not learning what the Maze was for.

A Walk Among the Tombstones—When Liam Neeson tells somebody, in that soft, deep, almost apologetic tone of his, that they’re in trouble if they harm some innocent victim, it’s hard not to take his threats seriously. Thus he’s making quite a career out of playing haunted father-figure rescuers and avengers, in melodramas like Taken and Taken 2, The Grey, Non-Stop and now A Walk Among the Tombstones.

Well, it’s certainly not a Tiptoe Through the Tulips. Based on one of the Lawrence Block novels about Matthew Scudder, an ex-NYPD recovering alcoholic and unlicensed private detective, the movie is a parade of horrors, starting us off with a gruesome shoot-out before the opening credits and getting much more unsavory from there. It’s set in 1999, against the backdrop of Y2K anxiety—how quaint does that seem now?—and involves a revolting kidnapping operation run by two of the most loathsome villains (David Harbour and Adam David Thompson) to turn up in a thriller in years.

Scudder (Neeson) is hired to find these two by a swanky drug trafficker (Dan Stevens) whose wife ended up dead even though he paid the ransom. All manner of twists are unraveled, Scudder’s horrifying guilty past is revealed, and our hero also befriends a homeless teenager (Bryan “Astro” Bradley) who wants to be a detective, before the big showdown in the graveyard between good and evil—or, rather, between evil and comparatively good—arrives.

Nasty though it is, I found this Jacobean Big Apple bloodbath intense and satisfying. The script, adapted by director Scott Frank, has some creaky passages, and the strand with the teenage kid bumps up against sentimentality, though it’s well played and it allows Neeson some lighter moments. But Frank’s direction, with his measured pacing and his melancholic atmosphere reminiscent of a certain style of ‘70s urban crime thriller, is really expert.

As the movie progressed, however, I became increasingly aware that these villains were so odious that no comeuppance would be sufficient to calm my vengeful bloodlust toward them. And indeed, it wasn’t sufficient. But that’s my spiteful heart’s problem, not the movie’s.

Thursday, September 18, 2014

MUTOS GRACIAS

Out on DVD this week is the uneven new Yank version of Godzilla...

...in which the title beast faces off against…

Monster-of-the-Week: …the “Massive Unidentified Terrestrial Organisms,” or MUTOs. I confess that I found these big geometrical buglike menaces somewhat lacking in personality, but they did, at least, have a fine sense of ponderousness, so let’s make the “Winged MUTO…”

…this week’s honoree.

...in which the title beast faces off against…

Monster-of-the-Week: …the “Massive Unidentified Terrestrial Organisms,” or MUTOs. I confess that I found these big geometrical buglike menaces somewhat lacking in personality, but they did, at least, have a fine sense of ponderousness, so let’s make the “Winged MUTO…”

…this week’s honoree.

Friday, September 12, 2014

RETALE

The main dolphin in the Dolphin Tale movies is tail-less. An injured bottlenose rescued in Florida, “Winter” was given a prosthetic tail which corrected her swimming motion, and became a star at the Clearwater Marine Aquarium. She played herself in 2011’s Dolphin Tale, a heavily fictionalized account of her life.

Winter’s back in Dolphin Tale 2, bereaved after the death, of old age, of a beloved tankmate. We’re shown how she bonds with a new foundling, an adorable baby bottlenose named Hope. Much of the movie’s focus, however, is on Sawyer (Nathan Gamble), the teen kid who found Winter in Part One, and his pal Hazel (Cozi Zuehlsdorff), the daughter of CMA’s founder (Harry Connick, Jr.).

These are pleasant enough kids, and some name players return to pick up a check as well—along with Connick, there’s Ashley Judd as Sawyer’s Mom, Kris Kristofferson as Connick’s Dad, and a smiling Morgan Freeman as the prosthetic designer, absolutely failing to convince us that he’s a curmudgeon. Surfer Bethany Hamilton, who lost an arm to a shark in 2003 and thus presumably feels some commonality with Winter, appears briefly as herself. Writer-director Charles Martin Smith turns up onscreen as well, as a cetological bureaucrat, and it’s nice to see him returning to his former, highly useful career as a character actor.

But for the kids in the audience, of course, the real stars of Dolphin Tale 2 are the animals—not just Winter and Hope but also a sea turtle and a comic-relief pelican. Smith could perhaps have used more of these creatures and less of the teen drama stuff, but he keeps things light and colorful, and at the end we’re shown real video footage of some of the rescues and releases depicted in the movie, seemingly just to quiet any suspicions we may have that this Tale is tall.

Winter’s back in Dolphin Tale 2, bereaved after the death, of old age, of a beloved tankmate. We’re shown how she bonds with a new foundling, an adorable baby bottlenose named Hope. Much of the movie’s focus, however, is on Sawyer (Nathan Gamble), the teen kid who found Winter in Part One, and his pal Hazel (Cozi Zuehlsdorff), the daughter of CMA’s founder (Harry Connick, Jr.).

These are pleasant enough kids, and some name players return to pick up a check as well—along with Connick, there’s Ashley Judd as Sawyer’s Mom, Kris Kristofferson as Connick’s Dad, and a smiling Morgan Freeman as the prosthetic designer, absolutely failing to convince us that he’s a curmudgeon. Surfer Bethany Hamilton, who lost an arm to a shark in 2003 and thus presumably feels some commonality with Winter, appears briefly as herself. Writer-director Charles Martin Smith turns up onscreen as well, as a cetological bureaucrat, and it’s nice to see him returning to his former, highly useful career as a character actor.

But for the kids in the audience, of course, the real stars of Dolphin Tale 2 are the animals—not just Winter and Hope but also a sea turtle and a comic-relief pelican. Smith could perhaps have used more of these creatures and less of the teen drama stuff, but he keeps things light and colorful, and at the end we’re shown real video footage of some of the rescues and releases depicted in the movie, seemingly just to quiet any suspicions we may have that this Tale is tall.

Thursday, September 11, 2014

MOSS APPEAL

RIP to the titanic Richard Kiel, passed on at 74. The 7-foot-plus fellow is of course best remembered as the indefatigable and curiously endearing “Jaws” in the Bond films The Spy Who Loved Me and Moonraker, and as the title caveman in the 1962 laugh-riot Eegah, but he played innumerable other towering menaces, including…

Monster-of-the-Week: …Pere Malfait, the mossy giant of Cajun lore in “The Spanish Moss Murders,” a 1974 episode of Kolchak: The Night Stalker…

This murky still does little justice to the creature’s creepiness in the show.

Friday, September 5, 2014

TWIN/FLYNN

New this week:

The Identical—The King of Rock n’ Roll might only have been the Prince of Rock and Roll if his twin brother hadn’t been stillborn. But as Elvis fans know, Jessie Garon Presley didn’t make it into the world alive. This movie wonders what might have happened if both brothers had survived, but nonetheless had been separated at birth.

Dirt-poor struggling parents (Brian Geraghty and Amanda Crew), barely able to care for one of their newborn twins in Depression-era Alabama, keep “Drexel Hemsley” but donate his brother Ryan to a kindly traveling evangelist (Ray Liotta!) and his wife (Ashley Judd) who are unable to have children of their own. The Reverend promises not to tell Ryan about his origin until the biological folks have died. Drexel goes on to become a star, but Ryan’s dad insists on grooming him for the ministry, even though the boy feels stirrings in his hips of a different calling when he hears roadhouse music. People are always telling Ryan how much he resembles Drexel, and eventually he hits the road with what would now be called a tribute act, and cleans up.

There’s an undeniable fairy-tale power to this premise that could have given it a Shakespearean wonder. But The Identical, though it appears to have had a fairly generous budget, comes across amateurish, emasculated, anachronism-riddled and inhibited. I can’t say I found it dull, but it’s been a while since a movie this cringe-inducingly kitschy got a wide release.

The moviemakers may themselves be evangelicals; Ryan is the most chaste and wholesome rock-and-roller imaginable—even Ricky Nelson and Frankie Avalon were bigger bad boys than this guy; it’s possible even Pat Boone was. Commendable though his behavior may be, it misses a major source of the appeal of rock music in general and of Presley in particular.

The movie’s religious interests also show up in the form of several apropos-of-nothing-much shout-outs to the State of Israel, and near the beginning, Rev. Liotta, preaching in a revival tent, tells his flock that black and white, Jew and gentile are all the same in the eyes of God. It’s uncertain if other categories of belief or race are included under this assertion; in any case, I found myself wondering how safe saying this would be, in Alabama in 1935, even for a white preacher.

The twins are both played, as adults, by Blake Rayne, who bears a good-enough-to-get-work-in-Vegas resemblance to the King, both physically and vocally. He’s also a rather sweet and likable screen presence, and the various hairstyles inflicted on him throughout the film increase both our sympathy for him and the comedy value of the movie.

As with That Thing You Do!, the music is ersatz—one of the movie’s many other (presumably unintentional) hilarities comes when the narrator (Ryan’s wife, played by the very cute Erin Cottrell), tells us that rock and roll may have been born the night that Ryan got up and sang in a roadhouse. Then the song he breaks into is presciently titled “Boogie-Woogie Rock n’ Roll"

The Last of Robin Hood—A pop culture icon is much more convincingly embodied in this chronicle of the last years of Errol Flynn. By the mid-‘50s the star was getting a bit mature for swashbuckling even if he hadn’t wrecked himself with booze and other indulgences, which he had. But he was still a name, and a charmer, and managed to win the heart of a young dancer and bit player named Beverly Aadland, who became the last love of his life. His final feature, Cuban Rebel Girls, was a painful low-budget 1959 indie built both as a vehicle for Aadland and as propaganda for Fidel Castro.

Just how young Aadland was when she and Flynn first got together, he supposedly didn’t know, at least at first. Suffice to say she was seriously underage, passing as years older than she really was so that she could work in movies. This was all with the complicity of her hardcore stage mother Florence, once a dancing hopeful herself until an accident claimed one of her legs. Florence eventually became complicit in Beverly’s affair with Flynn, too.

Kevin Kline plays Flynn, Dakota Fanning plays Beverly and Susan Sarandon plays Florence in The Last of Robin Hood. While a few other actors are shooed past the camera—including Max Casella as the young Stanley Kubrick, who reputedly considered Flynn for Humbert Humbert in Lolita—the focus is on the psychodrama between the three leads, and the writing/directing team of Richard Glatzer and Wash Westmoreland manage it briskly, with a plausible feel for how this dance of ego and desperation and self-delusion and vicarious gratification and, yes, true love could be kept going.

Kline, already 16 years older than Flynn was when he died, looks far better than the star did in the period depicted, but he catches Flynn’s disarming mix of suavity and self-deprecation, and how he could use a hint of rueful insecurity over his faded glamour to his advantage. He’s excellent, but in the long run Fanning and Sarandon carry the movie with their tense, textured interchanges.

The movie is slight, and there are a few scenes—one involves two punks shooting at Sarandon with an air rifle—that teeter precariously on the edge of camp. But The Last of Robin Hood is well-paced, and its period flavor is generated resourcefully on what was probably a pretty modest budget. Best of all, it’s witty without being catty and heartless—it remembers that these people are human beings, and that one of them was a kid.

The Identical—The King of Rock n’ Roll might only have been the Prince of Rock and Roll if his twin brother hadn’t been stillborn. But as Elvis fans know, Jessie Garon Presley didn’t make it into the world alive. This movie wonders what might have happened if both brothers had survived, but nonetheless had been separated at birth.

Dirt-poor struggling parents (Brian Geraghty and Amanda Crew), barely able to care for one of their newborn twins in Depression-era Alabama, keep “Drexel Hemsley” but donate his brother Ryan to a kindly traveling evangelist (Ray Liotta!) and his wife (Ashley Judd) who are unable to have children of their own. The Reverend promises not to tell Ryan about his origin until the biological folks have died. Drexel goes on to become a star, but Ryan’s dad insists on grooming him for the ministry, even though the boy feels stirrings in his hips of a different calling when he hears roadhouse music. People are always telling Ryan how much he resembles Drexel, and eventually he hits the road with what would now be called a tribute act, and cleans up.

There’s an undeniable fairy-tale power to this premise that could have given it a Shakespearean wonder. But The Identical, though it appears to have had a fairly generous budget, comes across amateurish, emasculated, anachronism-riddled and inhibited. I can’t say I found it dull, but it’s been a while since a movie this cringe-inducingly kitschy got a wide release.

The moviemakers may themselves be evangelicals; Ryan is the most chaste and wholesome rock-and-roller imaginable—even Ricky Nelson and Frankie Avalon were bigger bad boys than this guy; it’s possible even Pat Boone was. Commendable though his behavior may be, it misses a major source of the appeal of rock music in general and of Presley in particular.

The movie’s religious interests also show up in the form of several apropos-of-nothing-much shout-outs to the State of Israel, and near the beginning, Rev. Liotta, preaching in a revival tent, tells his flock that black and white, Jew and gentile are all the same in the eyes of God. It’s uncertain if other categories of belief or race are included under this assertion; in any case, I found myself wondering how safe saying this would be, in Alabama in 1935, even for a white preacher.

The twins are both played, as adults, by Blake Rayne, who bears a good-enough-to-get-work-in-Vegas resemblance to the King, both physically and vocally. He’s also a rather sweet and likable screen presence, and the various hairstyles inflicted on him throughout the film increase both our sympathy for him and the comedy value of the movie.

As with That Thing You Do!, the music is ersatz—one of the movie’s many other (presumably unintentional) hilarities comes when the narrator (Ryan’s wife, played by the very cute Erin Cottrell), tells us that rock and roll may have been born the night that Ryan got up and sang in a roadhouse. Then the song he breaks into is presciently titled “Boogie-Woogie Rock n’ Roll"

The Last of Robin Hood—A pop culture icon is much more convincingly embodied in this chronicle of the last years of Errol Flynn. By the mid-‘50s the star was getting a bit mature for swashbuckling even if he hadn’t wrecked himself with booze and other indulgences, which he had. But he was still a name, and a charmer, and managed to win the heart of a young dancer and bit player named Beverly Aadland, who became the last love of his life. His final feature, Cuban Rebel Girls, was a painful low-budget 1959 indie built both as a vehicle for Aadland and as propaganda for Fidel Castro.

Just how young Aadland was when she and Flynn first got together, he supposedly didn’t know, at least at first. Suffice to say she was seriously underage, passing as years older than she really was so that she could work in movies. This was all with the complicity of her hardcore stage mother Florence, once a dancing hopeful herself until an accident claimed one of her legs. Florence eventually became complicit in Beverly’s affair with Flynn, too.

Kevin Kline plays Flynn, Dakota Fanning plays Beverly and Susan Sarandon plays Florence in The Last of Robin Hood. While a few other actors are shooed past the camera—including Max Casella as the young Stanley Kubrick, who reputedly considered Flynn for Humbert Humbert in Lolita—the focus is on the psychodrama between the three leads, and the writing/directing team of Richard Glatzer and Wash Westmoreland manage it briskly, with a plausible feel for how this dance of ego and desperation and self-delusion and vicarious gratification and, yes, true love could be kept going.

Kline, already 16 years older than Flynn was when he died, looks far better than the star did in the period depicted, but he catches Flynn’s disarming mix of suavity and self-deprecation, and how he could use a hint of rueful insecurity over his faded glamour to his advantage. He’s excellent, but in the long run Fanning and Sarandon carry the movie with their tense, textured interchanges.

The movie is slight, and there are a few scenes—one involves two punks shooting at Sarandon with an air rifle—that teeter precariously on the edge of camp. But The Last of Robin Hood is well-paced, and its period flavor is generated resourcefully on what was probably a pretty modest budget. Best of all, it’s witty without being catty and heartless—it remembers that these people are human beings, and that one of them was a kid.

Thursday, September 4, 2014

DOUBLE DOG DARE

This Saturday Turner Classic Movies, the greatest TV channel of all time, presents 1981’s Clash of the Titans, the last of Ray Harryhausen’s stop-motion spectacles (check the TCM schedule for local airtimes). So…

Monster-of-the-Week: …this week let’s give the nod to “Dioskilos,” a variation on Cerberus with two heads instead of three…

…with whom Perseus and pals clash in the course of their adventure. I wonder if a spray bottle of water—or maybe two spray bottles, one in each hand—would have helped the poor creature’s behavior?

As for why Harryhausen decided that two heads were better three, it was probably for the same reason that his “It” in It Came From Beneath the Sea...

...was a “hexapus” rather than an octopus—fewer appendages, faster animation.

Monster-of-the-Week: …this week let’s give the nod to “Dioskilos,” a variation on Cerberus with two heads instead of three…

…with whom Perseus and pals clash in the course of their adventure. I wonder if a spray bottle of water—or maybe two spray bottles, one in each hand—would have helped the poor creature’s behavior?

As for why Harryhausen decided that two heads were better three, it was probably for the same reason that his “It” in It Came From Beneath the Sea...

...was a “hexapus” rather than an octopus—fewer appendages, faster animation.