As I have for the past two years, this year for no particularly good reason I again kept a list of the books I read. Here it is (it doesn’t include articles, reviews, essays, short stories, poems, comics, blogs, etc, or books I re-read):

Israel Potter: His Fifty Years of Exile by Herman Melville

Zombie Spaceship Wasteland by Patton Oswalt

Manhood for Amateurs by Michael Chabon

The Fatal Eggs by Mikhail Bulgakov

The Pharaoh’s Ghost by Kenneth Robeson

Barnabas, Quentin and the Grave-Robbers by Marilyn Ross

The Plebeians Rehearse the Uprising by Gunter Grass

The Fortune Cookie Chronicles by Jennifer 8 Lee

Tarzan at the Earth’s Core by Edgar Rice Burroughs

Tarzan and the Ant Men by Edgar Rice Burroughs

Armageddon 2419 A.D. by Philip Francis Nowlan

Tom Swift and His Flying Lab by Victor Appleton II

Sin-Ema by Steve Shadow

Unknown Man No. 89 by Elmore Leonard

The Optimist’s Daughter by Eudora Welty

Tarzan and "the Foreign Legion” by Edgar Rice Burroughs

Life of Pi by Yann Martel

Gracie: A Love Story by George Burns

Interventions by Richard Russo

The Ponder Heart by Eudora Welty

You may notice that I got on a Tarzan kick this year. I wasn’t alone—apparently a new Tarzan movie is in the works. Earlier this year the Erie Playhouse in my hometown successfully staged Disney’s Tarzan musical. Somehow Tarzan never quite goes away, not even at the age of one hundred, which he turned this year—Tarzan of the Apes was first published in 1912.

Put in a cranky Edgar Rice Burroughs-reading mood by my disappointment with the film John Carter, I reread the original Tarzan of the Apes earlier this year—it’s still a fine read, and has, for me, the most improbably touching last line of any American novel I can think of. Then I went on to several of ERB’s subsequent Tarzan tales that I had never caught up with: Tarzan at the Earth’s Core (1929), Tarzan and the Ant Men (1924) and Tarzan and "the Foreign Legion” (1947).

Earth’s Core was a fairly straightforward adventure yarn which took the Jungle Lord and some pals on a rescue mission (via German Zeppelin!) to Pellucidar, ERB’s inner-earth of endless, time-eradicating daylight. Ant Men, in which Tarz falls in with a race of mini-warriors in a remote part of Africa, was perhaps the best-written and wittiest ERB book I’ve ever read, full of charming Swiftian invention, yet the ideas behind its satire are appallingly, embarrassingly reactionary and sexist.

Maybe most interesting, however, was Tarzan and "the Foreign Legion,” the last Tarzan book Burroughs completed, while he was stationed as a war correspondent in Hawaii in WWII. The book is unapologetic propaganda—the quotation marks in the title are ERB’s, as it refers not to the French Foreign Legion, but to a ragtag assembly of American, Dutch, Chinese and native allies with whom Tarz finds himself stranded in the Sumatran jungle, making trouble for the Japanese.

The anti-“Jap” invective in the book is really venomous, yet the attitude toward strong, combat-capable women—one of them bi-racial!—is, in his usual boyishly bashful way, admiring. Don’t get me wrong—I’m not suggesting that ERB was a misunderstood early feminist. To read and enjoy his books today, one must look past a wince-inducing set of presumptions about class and race and gender (of course, this is true when reading Shakespeare, too). But ERB’s attitudes, though antiquated, are complex and reflective, and rarely mean-spirited.

RIP to puppet master Gerry Anderson of Thunderbirds, Captain Scarlet and Space: 1999 fame, passed on at 83.

Happy New Year everybody!

Monday, December 31, 2012

Friday, December 28, 2012

GONER

The Japanese filmmaker Shohei Imamura, who died in 2006, is probably best known in the US—by me, anyway—for Black Rain, his 1989 film about Hiroshima and its aftermath. This adaptation, in stunning black-and-white, of Masuji Abuse’s novel is gentle and heartbreakingly stoic. I think it was one of the great achievements in world cinema of the ‘80s, though it was understandably a bit of a tough sell as a critical recommendation.

Now the fearless folks at Icarus Films are trying to expand Imamura’s profile here in the west, with their release of his fascinating, atmospheric 1967 work A Man Vanishes (Ningen Johatsu), out this month on DVD. This feature-length investigation into the disappearance of a 30-year-old salesman begins as a documentary probe, but gradually turns into a verité-style mystery, with an ever-shifting take on the vanished man and on his enigmatic fiancé, who accompanies the director.

On various visual or thematic levels, the film may call to mind Citizen Kane, Rashomon, and some of Godard’s work. Yet it’s also a startling original, with Imamura pulling off a cheeky, admirable coup de cinema toward the end.

This Icarus Films edition also includes five short, intriguing Imamura documentaries for television, including 1971’s In Search of the Unreturned Soldiers in Malaysia, another investigation into vanished men—Imamura looks for, finds and interviews Japanese soldiers who blended into communities in Singapore and Malaysia after WWII ended. Some of their reasons for giving up their home country are, as is customary in Imamura’s work, unexpected.

Now the fearless folks at Icarus Films are trying to expand Imamura’s profile here in the west, with their release of his fascinating, atmospheric 1967 work A Man Vanishes (Ningen Johatsu), out this month on DVD. This feature-length investigation into the disappearance of a 30-year-old salesman begins as a documentary probe, but gradually turns into a verité-style mystery, with an ever-shifting take on the vanished man and on his enigmatic fiancé, who accompanies the director.

On various visual or thematic levels, the film may call to mind Citizen Kane, Rashomon, and some of Godard’s work. Yet it’s also a startling original, with Imamura pulling off a cheeky, admirable coup de cinema toward the end.

This Icarus Films edition also includes five short, intriguing Imamura documentaries for television, including 1971’s In Search of the Unreturned Soldiers in Malaysia, another investigation into vanished men—Imamura looks for, finds and interviews Japanese soldiers who blended into communities in Singapore and Malaysia after WWII ended. Some of their reasons for giving up their home country are, as is customary in Imamura’s work, unexpected.

Thursday, December 27, 2012

CHARACTERS

A couple of bigtime, landmark RIPs: first, to quintessential American character actor (and war hero) Charles Durning, passed on at 89.

Out of his countless memorable moments onscreen, in films ranging from The Sting to Dog Day Afternoon to Starting Over to Tootsie to The Muppet Movie to True Confessions to When a Stranger Calls to Dark Night of the Scarecrow to O Brother, Where Art Thou? and more, he may never have put on a show of equal parts performing skill and joy as this one, from 1982’s The Best Little Whorehouse in Texas. Few actors ever do. Watch it, if you want to smile.

The Wife and I were lucky enough to see Durning live, at the Orpheum Theatre in Phoenix in 1998, in a touring production of The Gin Game, with Julie Harris. We were also lucky enough to see Jack Klugman live, opposite Tony Randall, in a touring production of The Odd Couple in the early ‘90s, benefitting The National Actors Theater. Klugman, who passed on Christmas Eve at 90, had already lost a vocal cord to cancer by then, but even rasping out the role of Oscar Madison, he was clearly audible throughout Gammage Auditorium, and his warmth and vigor came through perfectly.

This New Year’s Eve marks the 34th anniversary of the death of the one-of-a-kind comic artist Basil Wolverton, so...

Monster-of-the-Week: …let’s give the nod to this particularly smug representative of The Brain Bats of Venus, a Wolverton story from a 1952 issue of Mister Mystery…

A Happy, Safe, Prosperous New Year from Monster-of-the-week!

Out of his countless memorable moments onscreen, in films ranging from The Sting to Dog Day Afternoon to Starting Over to Tootsie to The Muppet Movie to True Confessions to When a Stranger Calls to Dark Night of the Scarecrow to O Brother, Where Art Thou? and more, he may never have put on a show of equal parts performing skill and joy as this one, from 1982’s The Best Little Whorehouse in Texas. Few actors ever do. Watch it, if you want to smile.

This New Year’s Eve marks the 34th anniversary of the death of the one-of-a-kind comic artist Basil Wolverton, so...

Monster-of-the-Week: …let’s give the nod to this particularly smug representative of The Brain Bats of Venus, a Wolverton story from a 1952 issue of Mister Mystery…

A Happy, Safe, Prosperous New Year from Monster-of-the-week!

Friday, December 21, 2012

MIDDLE-AGED CRAZIES

With This is 40, Judd Apatow brings two memorable supporting characters from his 2007 hit Knocked Up to center stage: Debbie and Pete, the heroine’s bickering sister and brother-in-law. It appears that the reason they were such successful characters in the earlier film is precisely because they were supporting characters. This is 40 is well-acted, and it’s not without laughs and strong scenes. But watching these two squabble for more than two hours is, ultimately, more ordeal than pleasure.

L.A. fashion boutique owner and mother of two Debbie, played by Leslie Mann—Mrs. Apatow—is a blonde beauty and a bright-eyed, freaky obsessive. Pete, played by Paul Rudd, manages a struggling record label (he’s gambled big on a Graham Parker album). He’s emotionally recessive in the face of the intensity of his wife and daughters. He regularly retreats to the bathroom when he doesn’t need to relieve himself, just to play handheld electronic games. But he’s not safe from his wife’s intrusion even there.

Even so, for some reason Pete comes off less sympathetically than Debbie, maybe because the underlying dynamic seems to be that he’s no longer in love with his wife—he sometimes fantasizes about being a widower—yet she’s still desperately fascinated by him. In real life, of course, Pete’s trapped and overloaded feelings could awaken compassion, as could his terror at the prospect of admitting to Debbie that they’re on the brink of ruin. But in the movies, even with the always-appealing Rudd playing him, he just seems like a detached skunk who’s not trying. When we see him weeping in his car at one point, the moment falls surprisingly flat.

The movie centers, way too loosely, on the lead-up to a joint 40th and “38th” birthday party for Pete and Debbie, respectively. But it pursues a profusion of subplots, from Debbie’s troubles with her shop employees (Megan Fox and Charlyne Yi) to the growing pains and Lost fixation of her older daughter (Maude Apatow, who’s excellent) to the daddy issues that fuel Debbie and Pete’s dysfunction. Pete’s Dad (Albert Brooks) is a jolly, outrageous deadbeat—with toddlers from his more recent wife!—who shamelessly leeches off his son. Debbie’s Dad (John Lithgow) is the ultimate absentee, a hotshot spinal surgeon who can’t even confidently remember the names of his granddaughters.

I like Apatow, a lot. Knocked Up and The 40-Year-Old Virgin are already classics, I think, two of the best American comedies of the past decade. But his instincts are way off here. He tries to give every little strand, down to Debbie’s efforts to quit smoking or Pete’s cupcake addiction, its own story arc and payoff, and it’s just too much. He lets scenes play too long, and overindulges what appear to be improvisations until they become unfunny.

There’s a lot that’s good about This is 40, and with some fairly merciless cutting it could probably have been made into a decent movie. Not a great one, though, I don’t think. The core situation—affluent married people find themselves facing middle age without having attained a perfectly satisfactory life—isn’t exactly unique, and it lacks the urgency of Apatow’s earlier films. After all, at least they aren’t still virgins.

Make no mistake, the athletic and acrobatic feats captured on film in Cirque du Soliel: Worlds Away are enough to make you believe in superheroes. The performers in the circus franchise’s feature film come across like some other, higher species; some Nietzschean improvement on Homo Sapiens. What they do with their bodies doesn’t seem possible, and yet there they are, clearly doing it.

Considering how jaw-dropping their abilities are, and their beauty and erotic presence, it’s hard to understand why the movie is a bit of a bore. The franchise, started in the early ‘80s by a pair of Canadian street performers, has grown into a worldwide empire, with shows on six continents. It’s a contemporary take on the circus—no animals, a New-Agey, music-driven style and unifying themes to the performances. Worlds Away, directed by Andrew Adamson of Shrek, showcases the seven Cirque du Soleil productions in Las Vegas alone.

I have friends who are serious fans and repeat customers of the live shows, but even they admit that the videos of the performances just aren’t the same. I’m inclined to believe them—I can see how witnessing this stuff live could be overwhelming. But while watching this movie, more than once my chin began to droop toward my chest.

There’s a little bit of story to Worlds Away. An extremely cute gamine (Erica Linz) goes to the circus. In the middle of the act, a hunky aerialist (Igor Zaripov) makes eye contact with her and, distracted by her extreme gamine cuteness, misses his trapeze and plummets into the ring. But instead of going splat, he plunges right through the dirt, and the gamine, rushing to his aid, falls through after him.

She finds herself in a strange alternative avant-garde circus dimension. For the rest of the movie she wanders, accompanied by a grim-looking clown (John Clarke) with a bad case of bed head, from tent to tent, in search of her hunk. Some of her encounters are visually magical—like a lovely staging of “Octopus’s Garden”—and all are eye-popping demonstrations of physical skill and prowess.

But this slender thread of plot isn’t enough to disguise what Cirque du Soleil: Worlds Away really is—a commercial, first of all, but also a concert movie. And I would propose that the concert movie, with a handful of rule-proving exceptions, may be the most wearying of all film genres, blunting as it does both the immediacy and excitement of live performance and the narrative pull of cinema.

Oh yeah, it’s in 3-D. I honestly can’t remember one particularly striking effect that this added to the film.

L.A. fashion boutique owner and mother of two Debbie, played by Leslie Mann—Mrs. Apatow—is a blonde beauty and a bright-eyed, freaky obsessive. Pete, played by Paul Rudd, manages a struggling record label (he’s gambled big on a Graham Parker album). He’s emotionally recessive in the face of the intensity of his wife and daughters. He regularly retreats to the bathroom when he doesn’t need to relieve himself, just to play handheld electronic games. But he’s not safe from his wife’s intrusion even there.

Even so, for some reason Pete comes off less sympathetically than Debbie, maybe because the underlying dynamic seems to be that he’s no longer in love with his wife—he sometimes fantasizes about being a widower—yet she’s still desperately fascinated by him. In real life, of course, Pete’s trapped and overloaded feelings could awaken compassion, as could his terror at the prospect of admitting to Debbie that they’re on the brink of ruin. But in the movies, even with the always-appealing Rudd playing him, he just seems like a detached skunk who’s not trying. When we see him weeping in his car at one point, the moment falls surprisingly flat.

The movie centers, way too loosely, on the lead-up to a joint 40th and “38th” birthday party for Pete and Debbie, respectively. But it pursues a profusion of subplots, from Debbie’s troubles with her shop employees (Megan Fox and Charlyne Yi) to the growing pains and Lost fixation of her older daughter (Maude Apatow, who’s excellent) to the daddy issues that fuel Debbie and Pete’s dysfunction. Pete’s Dad (Albert Brooks) is a jolly, outrageous deadbeat—with toddlers from his more recent wife!—who shamelessly leeches off his son. Debbie’s Dad (John Lithgow) is the ultimate absentee, a hotshot spinal surgeon who can’t even confidently remember the names of his granddaughters.

I like Apatow, a lot. Knocked Up and The 40-Year-Old Virgin are already classics, I think, two of the best American comedies of the past decade. But his instincts are way off here. He tries to give every little strand, down to Debbie’s efforts to quit smoking or Pete’s cupcake addiction, its own story arc and payoff, and it’s just too much. He lets scenes play too long, and overindulges what appear to be improvisations until they become unfunny.

There’s a lot that’s good about This is 40, and with some fairly merciless cutting it could probably have been made into a decent movie. Not a great one, though, I don’t think. The core situation—affluent married people find themselves facing middle age without having attained a perfectly satisfactory life—isn’t exactly unique, and it lacks the urgency of Apatow’s earlier films. After all, at least they aren’t still virgins.

Make no mistake, the athletic and acrobatic feats captured on film in Cirque du Soliel: Worlds Away are enough to make you believe in superheroes. The performers in the circus franchise’s feature film come across like some other, higher species; some Nietzschean improvement on Homo Sapiens. What they do with their bodies doesn’t seem possible, and yet there they are, clearly doing it.

Considering how jaw-dropping their abilities are, and their beauty and erotic presence, it’s hard to understand why the movie is a bit of a bore. The franchise, started in the early ‘80s by a pair of Canadian street performers, has grown into a worldwide empire, with shows on six continents. It’s a contemporary take on the circus—no animals, a New-Agey, music-driven style and unifying themes to the performances. Worlds Away, directed by Andrew Adamson of Shrek, showcases the seven Cirque du Soleil productions in Las Vegas alone.

I have friends who are serious fans and repeat customers of the live shows, but even they admit that the videos of the performances just aren’t the same. I’m inclined to believe them—I can see how witnessing this stuff live could be overwhelming. But while watching this movie, more than once my chin began to droop toward my chest.

There’s a little bit of story to Worlds Away. An extremely cute gamine (Erica Linz) goes to the circus. In the middle of the act, a hunky aerialist (Igor Zaripov) makes eye contact with her and, distracted by her extreme gamine cuteness, misses his trapeze and plummets into the ring. But instead of going splat, he plunges right through the dirt, and the gamine, rushing to his aid, falls through after him.

She finds herself in a strange alternative avant-garde circus dimension. For the rest of the movie she wanders, accompanied by a grim-looking clown (John Clarke) with a bad case of bed head, from tent to tent, in search of her hunk. Some of her encounters are visually magical—like a lovely staging of “Octopus’s Garden”—and all are eye-popping demonstrations of physical skill and prowess.

But this slender thread of plot isn’t enough to disguise what Cirque du Soleil: Worlds Away really is—a commercial, first of all, but also a concert movie. And I would propose that the concert movie, with a handful of rule-proving exceptions, may be the most wearying of all film genres, blunting as it does both the immediacy and excitement of live performance and the narrative pull of cinema.

Oh yeah, it’s in 3-D. I honestly can’t remember one particularly striking effect that this added to the film.

Thursday, December 20, 2012

ABOMINABLE SNOWMAN

With the re-release of Disney’s Monsters Inc. in 3-D this week…

Monster-of-the-Week: …let’s honor the rather Lovecraftian snowman the gang has made in this Christmas card…

Happy Holidays from Monster-of-the-Week!

Monster-of-the-Week: …let’s honor the rather Lovecraftian snowman the gang has made in this Christmas card…

Happy Holidays from Monster-of-the-Week!

Tuesday, December 18, 2012

PRIZE DOES MATTER

Phoenix Film Critics Society, of which I’m proud to note that I’m a founding member, has announced its 2012 award winners. Like every year, some of these reflect my nominating and voting, some don’t, but as always there are lots of movies worth seeing on this list:

Phoenix Film Critics Society 2012 Annual Awards

Best Picture

Argo

Top Ten Films

Argo

The Avengers

Beasts of the Southern Wild

Les Misérables

Life of Pi

Lincoln

Moonrise Kingdom

Silver Linings Playbook

Skyfall

Zero Dark Thirty

Best Director

Kathryn Bigelow - Zero Dark Thirty

Best Actor in a Leading Role

Daniel Day-Lewis - Lincoln

Best Actress in a Leading Role

Jessica Chastain - Zero Dark Thirty

Best Actor in a Supporting Role

Philip Seymour Hoffman - The Master

Best Actress in a Supporting Role

Anne Hathaway - Les Misérables

Best Ensemble Acting

Moonrise Kingdom

Best Screenplay Written Directly for the Screen

Moonrise Kingdom

Best Screenplay Adapted from Another Medium

Argo

Best Live Action Family Film

Life of Pi

Overlooked Film of the Year

Safety Not Guaranteed

Best Animated Film

Wreck-It Ralph

Best Foreign Language Film

The Intouchables

Best Documentary

Searching for Sugar Man

Best Original Song

"Skyfall" from Skyfall

Best Original Score

Skyfall

Best Cinematography

Life of Pi

Best Film Editing

Argo

Best Production Design

Moonrise Kingdom

Best Costume Design

Anna Karenina

Best Visual Effects

Life of Pi

Best Stunts

Skyfall

Breakthrough Performance on Camera

Quvenzhané Wallis - Beasts of the Southern Wild

Breakthrough Performance Behind the Camera

Benh Zeitlin - Beasts of the Southern Wild

Best Youth Performance in a Lead or Supporting Role - Male

Tom Holland - The Impossible

Best Youth Performance in a Lead or Supporting Role - Female

Quvenzhané Wallis - Beasts of the Southern Wild

Assuming the Mayans weren’t right, my Top Ten list should be posted here shortly after the New Year.

Phoenix Film Critics Society 2012 Annual Awards

Best Picture

Argo

Top Ten Films

Argo

The Avengers

Beasts of the Southern Wild

Les Misérables

Life of Pi

Lincoln

Moonrise Kingdom

Silver Linings Playbook

Skyfall

Zero Dark Thirty

Best Director

Kathryn Bigelow - Zero Dark Thirty

Best Actor in a Leading Role

Daniel Day-Lewis - Lincoln

Best Actress in a Leading Role

Jessica Chastain - Zero Dark Thirty

Best Actor in a Supporting Role

Philip Seymour Hoffman - The Master

Best Actress in a Supporting Role

Anne Hathaway - Les Misérables

Best Ensemble Acting

Moonrise Kingdom

Best Screenplay Written Directly for the Screen

Moonrise Kingdom

Best Screenplay Adapted from Another Medium

Argo

Best Live Action Family Film

Life of Pi

Overlooked Film of the Year

Safety Not Guaranteed

Best Animated Film

Wreck-It Ralph

Best Foreign Language Film

The Intouchables

Best Documentary

Searching for Sugar Man

Best Original Song

"Skyfall" from Skyfall

Best Original Score

Skyfall

Best Cinematography

Life of Pi

Best Film Editing

Argo

Best Production Design

Moonrise Kingdom

Best Costume Design

Anna Karenina

Best Visual Effects

Life of Pi

Best Stunts

Skyfall

Breakthrough Performance on Camera

Quvenzhané Wallis - Beasts of the Southern Wild

Breakthrough Performance Behind the Camera

Benh Zeitlin - Beasts of the Southern Wild

Best Youth Performance in a Lead or Supporting Role - Male

Tom Holland - The Impossible

Best Youth Performance in a Lead or Supporting Role - Female

Quvenzhané Wallis - Beasts of the Southern Wild

Assuming the Mayans weren’t right, my Top Ten list should be posted here shortly after the New Year.

Friday, December 14, 2012

HARD HOBBIT TO BREAK

It's a big movie weekend:

When I heard that Peter Jackson’s movie version of The Hobbit was to be another trilogy, I must admit that my heart sank. A trilogy was understandable in the case of Jackson’s massive adaptation of J. R. R. Tolkien’s Lord of the Rings because the novels were, well, you know, a trilogy.

But The Hobbit—the only book of Tolkien’s I‘ve ever read—was a one-off, a stand-alone work, self-contained, expansive but not overflowing. The tale’s subtitle is There and Back Again, but Jackson’s first third, The Hobbit: An Unexpected Journey, doesn’t even quite get us there, let alone back again.

The thought of this deferred gratification made me a little grumpy, but having seen the film, my reaction is—what the heck, why not? If Jackson wants to give The Hobbit this crazy, geeky, hyper-detailed treatment, and has both the imaginative and technical resources to offer one lushly splendid sequence after another, then sure, I’ll go along for the ride. Sword-and-sorcery isn’t a genre I have a particular fondness for, but Tolkien was a terrific storyteller, and Jackson is at least as good in his art, so this first Hobbit movie leaves you feeling in good hands, even if it’s not your usual cup of tea.

First published in 1937, and often classed as a children’s book, The Hobbit is the story of Bilbo Baggins, a member of the titular race of short, burrow-dwelling folk of a mythic fairy-tale past. Hobbits have big, hairy, usually bare feet and are characteristically comfort-loving, unadventurous sorts, but Bilbo gets pressed into service by his friend Gandalf, a human wizard, to go on a quest with a band of warrior dwarves to recover a treasure lost generations earlier to a dragon, Smaug. The unassuming Bilbo’s role in this band is as its “burglar,” and though he has no experience at larceny, he discovers a talent for it, and for other daring skills.

The episodic adventures involve encounters and/or battles with elves, trolls, orcs (goblins, that is), giant wolves, giant eagles, sled rabbits and other fanciful beings. Bilbo, charmingly played by Martin Freeman (and, in the frame story, by Ian Holm as an older hobbit), engages in a dual of wits with the lost, corrupted cave-dweller Gollum. Here as in the earlier films, Gollum is played, behind the CGI, by Andy Serkis, and again he’s the most compelling character: chilling yet deeply pitiable, and strangely likable.

So I found the movie highly entertaining, and if you’re a Tolkien freak you probably will even more so, though of course if you’re a Tolkien freak my recommendation is unlikely to mean much to you either way. But there was something about this movie I found distracting, even though I realize that it’s likely a generational and Pavlovian response.

The screening I saw was in 48-fps 3D, a high-frame-rate format which gives the images undeniable clarity and focus. But it also gives them, for me, the over-lit look of old-school broadcast video footage—much of the time, despite the beauty of the compositions and the kinetic smoothness of the action, it was hard for me to shake the sense that I was watching an unusually well-made episode of Masterpiece Theatre from the ‘70s. Or an episode of the Tom Baker vintage of Dr. Who. Or of Days of Our Lives.

I recognize that this probably has to do with my own childhood TV-watching associations, and that it’s unlikely to bother younger viewers. But if you grew up watching TV in the ‘70s, this Hobbit may bring you perplexing flashbacks of All in the Family, Sanford and Son and Barney Miller.

As the title suggests, Roger Michell’s period piece Hyde Park on Hudson is a British film set in the U.S. It is, in part, the story of a poor relation: Margaret “Daisy” Suckley (Laura Linney), and her longtime relationship with her (suitably distant) cousin, Franklin Delano Roosevelt (Bill Murray).

Daisy is rather mysteriously invited to keep the President company, they hit it off, and before long she’s become his mistress. She loves the role, even when the presence of Eleanor (Olivia Williams) and other more veteran women in his life leaves her standing around like a teenage girl with a crush. Linney seems too mature for her part, though she isn’t, and this eventually becomes an effective source of pathos.

The other side of the movie focuses on a 1939 visit to Roosevelt’s home in rural New York by George VI of Britain (Samuel West) and his wife (Olivia Colman)—the first-ever visit to the U.S. by British monarchs—in hopes of securing American help against the Nazis. As in The King’s Speech, George is presented as a nervous, stammering young guy, irritable at being in over his head but otherwise not a bad sort. It’s an odd episode—the implication that, four decades into the 20th Century, it still took a summit between their inbred bluebloods and our inbred bluebloods to decide the fate of the world would be comic if it weren’t infuriating.

These two plot strands never quite seem to connect in any meaningful way, and on the whole Hyde Park on Hudson is sort of slow and dawdling. It isn’t a particularly good picture, but it has many good individual scenes, and the cast is great—especially Murray, who disappears into the inscrutable FDR.

It wasn’t until after the movie was over that I thought about it—that was Carl from Caddyshack, and Winger from Stripes, yet it never occurred to me to giggle at him playing an iconic historical figure. He’s long since made the transition from comedy persona to full-service character actor. Cinderella boy, outta nowhere.

Valley moviegoers who can only get to one movie this weekend, however, should consider Arnon Goldfinger’s The Flat, presented by Greater Phoenix Jewish Film Festival at 2 p.m. Sunday at FilmBar. It’s a personal documentary with a quiet punch—a gradually rising tide of conflicted emotion.

It begins with Goldfinger and his family clearing out his grandmother’s Tel Aviv apartment after her death, at 98. Her books and tchochkes show that she remained culturally German, but this didn’t prepare Goldfinger for the revelation that his Zionist grandparents traveled to Palestine in the ‘30s…in the company of a Nazi and his wife.

Not just any Nazi, either, but Baron Leopold von Mildenstein, a writer for the ferociously anti-semitic Der Angriff, and later a bigwig with the SS. At the time Von Mildenstein was advocating the idea that German Jews could, as Mitt Romney might put it, “self-deport” to Palestine.

Goldfinger is startled to learn that Von Mildenstein and his father, both educated, sophisticated men, became friends on this trip, as did their wives. He’s flabbergasted when he later learns that after the war, they renewed the friendship. Before long he finds himself interviewing—almost interrogating—Von Mildenstein’s pleasant, warmhearted and utterly in-denial daughter, and his own almost more evasive mother.

The more he probes the mystery, the more baffled he becomes, and the more unsettling and ambiguous The Flat becomes. What keeps it from being depressing is the vividness of its portraits, including that of Goldfinger himself, reluctantly opening old wounds, but showing up for interviews with a nice bouquet. He’s like an apologetic Max Ophuls.

RIP to sitar master Ravi Shankar, passed on 91.

When I heard that Peter Jackson’s movie version of The Hobbit was to be another trilogy, I must admit that my heart sank. A trilogy was understandable in the case of Jackson’s massive adaptation of J. R. R. Tolkien’s Lord of the Rings because the novels were, well, you know, a trilogy.

But The Hobbit—the only book of Tolkien’s I‘ve ever read—was a one-off, a stand-alone work, self-contained, expansive but not overflowing. The tale’s subtitle is There and Back Again, but Jackson’s first third, The Hobbit: An Unexpected Journey, doesn’t even quite get us there, let alone back again.

The thought of this deferred gratification made me a little grumpy, but having seen the film, my reaction is—what the heck, why not? If Jackson wants to give The Hobbit this crazy, geeky, hyper-detailed treatment, and has both the imaginative and technical resources to offer one lushly splendid sequence after another, then sure, I’ll go along for the ride. Sword-and-sorcery isn’t a genre I have a particular fondness for, but Tolkien was a terrific storyteller, and Jackson is at least as good in his art, so this first Hobbit movie leaves you feeling in good hands, even if it’s not your usual cup of tea.

First published in 1937, and often classed as a children’s book, The Hobbit is the story of Bilbo Baggins, a member of the titular race of short, burrow-dwelling folk of a mythic fairy-tale past. Hobbits have big, hairy, usually bare feet and are characteristically comfort-loving, unadventurous sorts, but Bilbo gets pressed into service by his friend Gandalf, a human wizard, to go on a quest with a band of warrior dwarves to recover a treasure lost generations earlier to a dragon, Smaug. The unassuming Bilbo’s role in this band is as its “burglar,” and though he has no experience at larceny, he discovers a talent for it, and for other daring skills.

So I found the movie highly entertaining, and if you’re a Tolkien freak you probably will even more so, though of course if you’re a Tolkien freak my recommendation is unlikely to mean much to you either way. But there was something about this movie I found distracting, even though I realize that it’s likely a generational and Pavlovian response.

The screening I saw was in 48-fps 3D, a high-frame-rate format which gives the images undeniable clarity and focus. But it also gives them, for me, the over-lit look of old-school broadcast video footage—much of the time, despite the beauty of the compositions and the kinetic smoothness of the action, it was hard for me to shake the sense that I was watching an unusually well-made episode of Masterpiece Theatre from the ‘70s. Or an episode of the Tom Baker vintage of Dr. Who. Or of Days of Our Lives.

I recognize that this probably has to do with my own childhood TV-watching associations, and that it’s unlikely to bother younger viewers. But if you grew up watching TV in the ‘70s, this Hobbit may bring you perplexing flashbacks of All in the Family, Sanford and Son and Barney Miller.

As the title suggests, Roger Michell’s period piece Hyde Park on Hudson is a British film set in the U.S. It is, in part, the story of a poor relation: Margaret “Daisy” Suckley (Laura Linney), and her longtime relationship with her (suitably distant) cousin, Franklin Delano Roosevelt (Bill Murray).

Daisy is rather mysteriously invited to keep the President company, they hit it off, and before long she’s become his mistress. She loves the role, even when the presence of Eleanor (Olivia Williams) and other more veteran women in his life leaves her standing around like a teenage girl with a crush. Linney seems too mature for her part, though she isn’t, and this eventually becomes an effective source of pathos.

The other side of the movie focuses on a 1939 visit to Roosevelt’s home in rural New York by George VI of Britain (Samuel West) and his wife (Olivia Colman)—the first-ever visit to the U.S. by British monarchs—in hopes of securing American help against the Nazis. As in The King’s Speech, George is presented as a nervous, stammering young guy, irritable at being in over his head but otherwise not a bad sort. It’s an odd episode—the implication that, four decades into the 20th Century, it still took a summit between their inbred bluebloods and our inbred bluebloods to decide the fate of the world would be comic if it weren’t infuriating.

These two plot strands never quite seem to connect in any meaningful way, and on the whole Hyde Park on Hudson is sort of slow and dawdling. It isn’t a particularly good picture, but it has many good individual scenes, and the cast is great—especially Murray, who disappears into the inscrutable FDR.

It wasn’t until after the movie was over that I thought about it—that was Carl from Caddyshack, and Winger from Stripes, yet it never occurred to me to giggle at him playing an iconic historical figure. He’s long since made the transition from comedy persona to full-service character actor. Cinderella boy, outta nowhere.

Valley moviegoers who can only get to one movie this weekend, however, should consider Arnon Goldfinger’s The Flat, presented by Greater Phoenix Jewish Film Festival at 2 p.m. Sunday at FilmBar. It’s a personal documentary with a quiet punch—a gradually rising tide of conflicted emotion.

It begins with Goldfinger and his family clearing out his grandmother’s Tel Aviv apartment after her death, at 98. Her books and tchochkes show that she remained culturally German, but this didn’t prepare Goldfinger for the revelation that his Zionist grandparents traveled to Palestine in the ‘30s…in the company of a Nazi and his wife.

Not just any Nazi, either, but Baron Leopold von Mildenstein, a writer for the ferociously anti-semitic Der Angriff, and later a bigwig with the SS. At the time Von Mildenstein was advocating the idea that German Jews could, as Mitt Romney might put it, “self-deport” to Palestine.

Goldfinger is startled to learn that Von Mildenstein and his father, both educated, sophisticated men, became friends on this trip, as did their wives. He’s flabbergasted when he later learns that after the war, they renewed the friendship. Before long he finds himself interviewing—almost interrogating—Von Mildenstein’s pleasant, warmhearted and utterly in-denial daughter, and his own almost more evasive mother.

The more he probes the mystery, the more baffled he becomes, and the more unsettling and ambiguous The Flat becomes. What keeps it from being depressing is the vividness of its portraits, including that of Goldfinger himself, reluctantly opening old wounds, but showing up for interviews with a nice bouquet. He’s like an apologetic Max Ophuls.

RIP to sitar master Ravi Shankar, passed on 91.

Thursday, December 13, 2012

OF ALL THE UNMITIGATED GOLLUM

With part one of Peter Jackson’s Hobbit trilogy opening tomorrow…

Monster-of-the-Week: …let’s give the nod to the creepy cave creature Gollum, as realized in the animated 1977 Rankin-Bass adaptation of The Hobbit…

The Big G was given voice in this show by the peerless Brother Theodore...

...and meaning no disrespect to the excellent Andy Serkis, Theodore could wrap his rasp around the word “Precious” like nobody else…

Monster-of-the-Week: …let’s give the nod to the creepy cave creature Gollum, as realized in the animated 1977 Rankin-Bass adaptation of The Hobbit…

The Big G was given voice in this show by the peerless Brother Theodore...

...and meaning no disrespect to the excellent Andy Serkis, Theodore could wrap his rasp around the word “Precious” like nobody else…

Monday, December 10, 2012

NEIL COHEN (1963-2012)

Hyperbole is common when the subject is somebody who has just died. But I promise you that I would have listed my friend and Phoenix Film Critic Society colleague Neil Cohen without hesitation as one of the nicest, sweetest people I’ve ever known—a human mood-lifter—even if he hadn’t passed on Saturday night. Which, alas, he did.

Neil was an actor and playwright as well as a critic, a longtime veteran of the Murder-Mystery dinner theater scene, and he succumbed to an apparent heart attack, backstage during a show he was performing in. That he died doing something he loved so much is a great comfort.

RIP, Neil. Be seeing you, pal. I’m so glad I got to chat with you a little after the screening Thursday night. I’ll miss you enormously. If you ever feel like dropping in on a screening, go for it.

Here’s Neil as Rhoda in his notorious production of The Bad Seed some years ago. Something tells me he’d like to be remembered this way…

Neil was an actor and playwright as well as a critic, a longtime veteran of the Murder-Mystery dinner theater scene, and he succumbed to an apparent heart attack, backstage during a show he was performing in. That he died doing something he loved so much is a great comfort.

RIP, Neil. Be seeing you, pal. I’m so glad I got to chat with you a little after the screening Thursday night. I’ll miss you enormously. If you ever feel like dropping in on a screening, go for it.

Here’s Neil as Rhoda in his notorious production of The Bad Seed some years ago. Something tells me he’d like to be remembered this way…

Saturday, December 8, 2012

TO SURROGATE, WITH LOVE

Here's a pair of gems, both playing here in the Valley, that I only caught up with recently…

Stricken with polio as a child, the poet and essayist Mark O’Brien spent most of his 49 years in an iron lung. He was the subject of the Oscar-winning 1996 documentary short Breathing Lessons (viewable here). Now, with The Sessions, his efforts to claim a satisfying sexuality, with the help of a sex surrogate, have gotten the full feature treatment from writer-director Ben Lewin (a polio survivor himself).

It’s a film of charming sweetness and easygoing wit, built around superb performances. John Hawkes, in another demonstration of his phenomenal range, is luminous as O’Brien, utterly convincing in his depiction of the man’s disability and vulnerability, but also of his indomitable spirit. The performance is both a technical tour de force and a blast of star quality.

Helen Hunt is no less a knockout as the surrogate, Cheryl Cohen Greene, with her gentle, comically frayed aplomb and her undercurrent of admiration for her client. Then there’s Moon Bloodgood as O’Brien’s unflappable aide, and William H. Macy, terrific as his priest, who gives O’Brien’s project the green light on behalf of the Church. Alas, this means listening to O’Brien’s accounts of it, and glumly reflecting on the unspoken irony that the guy in the iron lung has a better sex life than his.

Ben Affleck is one of those high-profile celebrities about whom it was fashionably decided, at some point, that he was a douchebag and a joke, fit only for ridicule. If this had not been the case, if he were judged only on the merits of his three films as a director—Gone Baby Gone, The Town and Argo—what would his reputation be? I think that he would already have been hailed as the best, or at least most promising, director of suspense movies since at least Costa-Gavras, if not Hitchcock himself.

Argo, now in theatres, is a dramatization of the CIA operation to extract from Tehran the six Americans who escaped the US Embassy before it was overrun by Iranian revolutionaries in 1979, and thus were not among the 52 hostages that were held there for 444 days. It’s essentially a caper movie about stealing people instead of diamonds or whatever.

The agent who designed and conducted the caper, a man named Tony Mendez (Affleck), concocted a bizarrely over-elaborate-seeming cover story in which he and the hostages, who had taken refuge at the home of the Canadian Ambassador to Iran (Victor Garber), masqueraded as filmmakers scouting locations for a science-fiction film, called Argo.

From his crisply-edited, scary opening sequence—the Embassy takeover—on, Affleck’s step as director seems entirely sure-footed. Obvious liberties are taken in several sequences, especially toward the end, for the sake of eminent peril and hairbreadth escape, and one could argue the necessity of taking the movie so far into old-school melodrama. But the success with which Affleck executes these flourishes is spectacular: The suspense is excruciating, though it’s also nicely leavened by comedy, both from the sour, mordant CIA guys—Bryan Cranston is at his best as Affleck’s boss—and, more broadly, from Alan Arkin and John Goodman as a baggy-pants team of Hollywood cronies helping Affleck fake the production (Goodman plays real-life makeup man John Chambers, the Oscar-winner behind the Planet of the Apes effects).

As for Affleck’s own haunted, low-key presence in the star part here, Argo suggests that not only is he a superb director, but that he’s better in front of the camera when he’s also behind the camera.

RIP to Susan Luckey, a hoot as Mayor Shinn’s daughter in The Music Man, passed on at 74. Ye gods, she was cute…

It’s a film of charming sweetness and easygoing wit, built around superb performances. John Hawkes, in another demonstration of his phenomenal range, is luminous as O’Brien, utterly convincing in his depiction of the man’s disability and vulnerability, but also of his indomitable spirit. The performance is both a technical tour de force and a blast of star quality.

Helen Hunt is no less a knockout as the surrogate, Cheryl Cohen Greene, with her gentle, comically frayed aplomb and her undercurrent of admiration for her client. Then there’s Moon Bloodgood as O’Brien’s unflappable aide, and William H. Macy, terrific as his priest, who gives O’Brien’s project the green light on behalf of the Church. Alas, this means listening to O’Brien’s accounts of it, and glumly reflecting on the unspoken irony that the guy in the iron lung has a better sex life than his.

Ben Affleck is one of those high-profile celebrities about whom it was fashionably decided, at some point, that he was a douchebag and a joke, fit only for ridicule. If this had not been the case, if he were judged only on the merits of his three films as a director—Gone Baby Gone, The Town and Argo—what would his reputation be? I think that he would already have been hailed as the best, or at least most promising, director of suspense movies since at least Costa-Gavras, if not Hitchcock himself.

Argo, now in theatres, is a dramatization of the CIA operation to extract from Tehran the six Americans who escaped the US Embassy before it was overrun by Iranian revolutionaries in 1979, and thus were not among the 52 hostages that were held there for 444 days. It’s essentially a caper movie about stealing people instead of diamonds or whatever.

The agent who designed and conducted the caper, a man named Tony Mendez (Affleck), concocted a bizarrely over-elaborate-seeming cover story in which he and the hostages, who had taken refuge at the home of the Canadian Ambassador to Iran (Victor Garber), masqueraded as filmmakers scouting locations for a science-fiction film, called Argo.

From his crisply-edited, scary opening sequence—the Embassy takeover—on, Affleck’s step as director seems entirely sure-footed. Obvious liberties are taken in several sequences, especially toward the end, for the sake of eminent peril and hairbreadth escape, and one could argue the necessity of taking the movie so far into old-school melodrama. But the success with which Affleck executes these flourishes is spectacular: The suspense is excruciating, though it’s also nicely leavened by comedy, both from the sour, mordant CIA guys—Bryan Cranston is at his best as Affleck’s boss—and, more broadly, from Alan Arkin and John Goodman as a baggy-pants team of Hollywood cronies helping Affleck fake the production (Goodman plays real-life makeup man John Chambers, the Oscar-winner behind the Planet of the Apes effects).

As for Affleck’s own haunted, low-key presence in the star part here, Argo suggests that not only is he a superb director, but that he’s better in front of the camera when he’s also behind the camera.

RIP to Susan Luckey, a hoot as Mayor Shinn’s daughter in The Music Man, passed on at 74. Ye gods, she was cute…

Thursday, December 6, 2012

(STAR) WAR ON CHRISTMAS

Friday evening at 6 p.m. Phoenix Art Museum hosts “A Very Merry Sci-Fi Christmas,” featuring a rare showing of The Star Wars Holiday Special…

This ghastly ‘70s-style variety TV show aired in the U.S. only once, in November of 1978. It’s been much repented-of, with characteristic humorlessness, by George Lucas, and is now regarded as sort of the deformed-relation-locked-in-the-attic of the Star Wars franchise. It marked the debut of fan favorite Boba Fett, and it’s the only Star Wars entry that includes an appearance by the great Bea Arthur. It’s almost too skin-crawlingly embarrassing to be hilarious. But only almost.

So…

Monster-of-the-Week: …let’s recognize the long-necked dragonish critter, a native of the viscous oceans of the planet Panna…

…from the Canadian cartoon included in the special.

RIP to the great Dave Brubeck, departed at 91.

So…

Monster-of-the-Week: …let’s recognize the long-necked dragonish critter, a native of the viscous oceans of the planet Panna…

…from the Canadian cartoon included in the special.

RIP to the great Dave Brubeck, departed at 91.

Thursday, November 29, 2012

MASS APPEAL

It’s claimed that Larry Hagman despised I Dream of Jeannie, the hit show in which he starred from 1965 to 1970. It’s a shame if so, because Hagman, who died last weekend at 81, was really good on it. He was likable as Major Anthony “Tony” Nelson, an astronaut who finds a genie in a bottle—gorgeous, magically all-powerful and unshakably devoted to him—which somehow turns his life into a door-slamming farce.

But he wasn’t only likable—as an actor, he was up to the demands of that farce. Although Barbara Eden, who played Jeannie, Bill Daily, who played Tony’s goofy fellow astronaut and pal Roger Healey, Hayden Rorke, who played their perpetually baffled superior Dr. Bellows, and others on the show were highly amusing, Hagman, son of musical-theatre great Mary Martin, was the energy that kept the silly, occasionally surreal stories buoyant. He was a gifted physical clown, very able to take a pratfall or a wide-eyed double take, or to let out a hilariously panicked bleat.

A product both of the vogue for fanciful sitcoms and of the enthusiasm for the space program in the mid-‘60s, the show grew its farcical situations out of Tony’s frantic efforts to keep Jeannie’s existence a secret, and to explain away the bizarre results of her magical shenanigans. As kids, a lot of us wondered why he bothered, but Hagman’s comic desperation was so infectious that it didn’t matter.

I grew up watching I Dream of Jeannie, and so remember Hagman much more vividly from that than from the role he reportedly liked better, that of snaky Texas oilman J. R. Ewing from the prime time soap opera Dallas. It was there that he made his most famous mark on pop culture, as the object of the “Who Shot J. R.?” cliffhanger. Though I well remember the craze, I wasn’t a Dallas viewer, so while my glimpses of the show suggested that Hagman indeed enjoyed playing J. R.’s rottenness to the gleeful hilt, he’ll always be the hapless Tony Nelson to me.

Hagman was also a director, of many episodes of Dallas and In the Heat of the Night and other shows, but of just one feature film, a favorite of mine…

Monster-of-the-Week: …1972’s Beware! The Blob! This facetious, and genuinely funny, sequel to the 1958 sci-fi classic The Blob has the title amorphous mass, this week’s honoree, coming back to life, this time to gobble up hippies and barbers and stoned egg farmers, eventually enveloping a bowling alley/skating rink.

In outline, it’s a standard creature-feature sequel; what makes it special are the set-piece ensemble scenes, many with an improv-comedy flavor, performed by a cast that includes Robert Walker, Jr., Godfrey Cambridge, Carol Lynley, Dick Van Patten, Cindy Williams, Marlene Clark, Shelley Berman, Del Close and an uncredited Burgess Meredith, among many others—in short, by one of the stronger casts that Hagman ever got to work with. The lovely leading lady, Gwynne Guilford, is the mother of the rising young star Chris Pine.

Long unavailable on video, Beware! The Blob! may be watched in its entirety here, and I highly recommend…with one caveat for sensitive souls: The cutest kitten in movie history cavorts under the opening titles; within minutes it’s blob-chow.

Later, the same thing happens to a cute little dog.

But he wasn’t only likable—as an actor, he was up to the demands of that farce. Although Barbara Eden, who played Jeannie, Bill Daily, who played Tony’s goofy fellow astronaut and pal Roger Healey, Hayden Rorke, who played their perpetually baffled superior Dr. Bellows, and others on the show were highly amusing, Hagman, son of musical-theatre great Mary Martin, was the energy that kept the silly, occasionally surreal stories buoyant. He was a gifted physical clown, very able to take a pratfall or a wide-eyed double take, or to let out a hilariously panicked bleat.

A product both of the vogue for fanciful sitcoms and of the enthusiasm for the space program in the mid-‘60s, the show grew its farcical situations out of Tony’s frantic efforts to keep Jeannie’s existence a secret, and to explain away the bizarre results of her magical shenanigans. As kids, a lot of us wondered why he bothered, but Hagman’s comic desperation was so infectious that it didn’t matter.

I grew up watching I Dream of Jeannie, and so remember Hagman much more vividly from that than from the role he reportedly liked better, that of snaky Texas oilman J. R. Ewing from the prime time soap opera Dallas. It was there that he made his most famous mark on pop culture, as the object of the “Who Shot J. R.?” cliffhanger. Though I well remember the craze, I wasn’t a Dallas viewer, so while my glimpses of the show suggested that Hagman indeed enjoyed playing J. R.’s rottenness to the gleeful hilt, he’ll always be the hapless Tony Nelson to me.

Hagman was also a director, of many episodes of Dallas and In the Heat of the Night and other shows, but of just one feature film, a favorite of mine…

Monster-of-the-Week: …1972’s Beware! The Blob! This facetious, and genuinely funny, sequel to the 1958 sci-fi classic The Blob has the title amorphous mass, this week’s honoree, coming back to life, this time to gobble up hippies and barbers and stoned egg farmers, eventually enveloping a bowling alley/skating rink.

Long unavailable on video, Beware! The Blob! may be watched in its entirety here, and I highly recommend…with one caveat for sensitive souls: The cutest kitten in movie history cavorts under the opening titles; within minutes it’s blob-chow.

Later, the same thing happens to a cute little dog.

Tuesday, November 27, 2012

THE NORMAN HEART

Out on DVD today: The excellent little stop-motion-animated kiddie-spooker ParaNorman.

It starts with the same premise as The Sixth Sense—a little boy who sees dead people. It’s up to Norman to figure out the secret that raises six rotted corpses from their graves and sends them shambling through the streets of the small town where he lives. The movie is imaginative, generous-hearted and funny, though with a surprisingly dramatic and poignant revelation at its core. Best of all, it avoids the sterility that haunts so many contemporary animated movies—Norman’s home town has a grubby, hardscrabble look, like a shop town down on its luck, that’s very refreshing.

It starts with the same premise as The Sixth Sense—a little boy who sees dead people. It’s up to Norman to figure out the secret that raises six rotted corpses from their graves and sends them shambling through the streets of the small town where he lives. The movie is imaginative, generous-hearted and funny, though with a surprisingly dramatic and poignant revelation at its core. Best of all, it avoids the sterility that haunts so many contemporary animated movies—Norman’s home town has a grubby, hardscrabble look, like a shop town down on its luck, that’s very refreshing.

Saturday, November 24, 2012

FROST HIT

Given his abstract-impressionist’s brush on window glass, you might imagine Jack Frost would be the artsy, snooty sort. But according to Rise of the Guardians, Jack’s a friendly, mischievous boy, eager for acceptance, dismayed that the kids who have him to thank for snow days and sledding fun can’t see him.

Jack, voiced by Chris Pine, is the hero of the computer-animated flick, conflated from William Joyce’s series of children’s books. The title characters are the legendary or allegorical figures who watch over childhood wonder, hopes and dreams. The others include Santa Claus, voiced like a radio-comedy Russian by Alec Baldwin, the Tooth Fairy, a winsome half-woman/half-hummingbird voiced by Isla Fisher, and the tough, Aussie-accented Easter Bunny (Hugh Jackman), who comes armed with a boomerang, but also has the tendency to leave a blooming flower in his burrow’s wake.

Best of all, maybe, is the Sandman, a roly-poly sort who doesn’t speak, but communicates by shaping his thoughts in sand over his head. They’ve all received their commissions from the omniscient—and thus, of course, highly enigmatic—Man in the Moon, and now it’s Jack Frost’s turn. If he becomes a full-fledged Guardian, then the kids may actually believe in him like they do Santa or the Bunny, and thus be able to catch a glimpse of him.

The menace is Pitch Black, aka the Boogeyman, given a nicely ironic, tut-tutting voice by Jude Law. Pitch is a simply pale figure in a brown robe, attended by a stamping herd of terrifying black horses—nightmares, of course.

Nostalgic for the Dark Ages, the salad days of terror and despair, Pitch looks to make a comeback, and he’s no minor adversary. So the Guardians must put aside their egos and grudges—even the Bunny, who resents Jack for the “Blizzard of ‘68” on Easter Sunday—and unify to defend childhood wonder.

Like last year’s fine Arthur Christmas, among other kid movies, Rise of the Guardians plays with the childhood desire to literalize and reconcile the difficult logistics connected to the duties of these symbolic figures, and does it in funny and imaginative ways. It also features an exciting action finale and many good jokes and some thrilling images, like the Sandman’s good dreams—sand-cast dinosaurs and sting-rays and dolphins—trooping to the rescue down suburban streets. That it’s not the best animated movie of the year testifies not to its weakness but to the genre’s strength these days.

Friday, November 23, 2012

HUSBAND AND KNIFE

It’s possible that I’m not the best judge of Hitchcock.

It’s a movie about the making of Sir Alfred’s 1960 classic Psycho, which is, truly, one of my two or three favorite movies. It has a fine cast, including a number of extremely attractive actresses, two of them—Scarlett Johansson and Jessica Biel—decked out in Psycho costumes. It’s set in an elegant recreation of Hollywood swank, circa the late ‘50s.

For all of these reasons, I enjoyed it. But I don’t know that even all of them together quite make it a good movie. Hitchcock, directed by Sacha Gervasi, from a script by John J. McLaughlin based on Stephen Rebello’s Alfred Hitchcock and the Making of Psycho, is fun to watch, but somehow I couldn’t quite find it convincing.

The main reason, I think, lies with the title personage. He’s played by Anthony Hopkins, padded and plastered to resemble the great man, to little avail. Powerhouse though Hopkins is, he couldn’t make me believe he was Alfred Hitchcock, or even simply forget he’s not Hitchcock, which might have been enough. It isn’t his fault—I don’t think any actor could. I haven’t seen the HBO movie The Girl, about the making of The Birds, but I hear Toby Jones doesn’t really swing it either.

The word “inimitable” is thrown around a lot in show business, but beyond the level of an easy Rich Little impression, Hitchcock really is inimitable, at least for someone of my generation. His canny on-camera self-promotion made him indelible to Boomer-era TV viewers and moviegoers. Nobody looks like that—for all the heroic efforts of the make-up folk, Hopkins looks more like late-vintage Rod Steiger than Hitchcock—nobody sounds like that, and nobody, I think, is really likely to capture that same grave drollery of manner. Hopkins gives a sometimes funny, sometimes touching portrait of a weird repressed middle-aged guy, but not of this particular weird repressed middle-aged guy.

Similarly, Hitchcock overplays its hand in dramatizing the making of Psycho. That film, as hardly anyone needs to be told, is Hitchcock’s modestly-budgeted, brilliantly-crafted California-gothic about Norman Bates, a sweet young motel manager who has an unusually close relationship with his mother—lethally close, to any strangers who encroach on it. It was adapted from a lurid little novel by Robert Bloch, which was in turn loosely based on the much grimmer real-life exploits of Wisconsin psychopath Ed Gein in 1957.

Hitchcock was slumming a bit when he took on the project, no doubt, challenging himself to make a profitable low-budget shocker, using the crew from his TV series, instead of the glamorous, romantic Technicolor thrillers he’d been turning out for the last decade or so. It’s doubtful he could have guessed he was making the movie for which he’d be best remembered.

Gervasi's film, on the other hand, tries to generate dramatic urgency by creating the sense that Psycho was a make-or-break crisis point in Hitchcock’s career. Much is made of Hitchcock’s own investment in the project, though the practical minded Mrs. H (Helen Mirren) points out that the peril to their fortune is along the lines of having to buy domestic rather than imported pate de fois gras. Gervasi and McLaughlin even resort to showing Hitchcock’s dreams haunted by the specter of Ed Gein (Michael Wincott). This feels like an overwrought reach.

So Hitchcock comes to life, mostly, in incidental episodes, and in the cast—James D’Arcy absolutely nailing the small role of Anthony Perkins, Toni Collette, ravishingly chic as Hitchcock’s right arm Peggy Robertson. Biel looks great as Vera Miles, and Johansson really did her homework as Janet Leigh, perfectly capturing Leigh’s pursed-lipped, mock-perplexed cock of the head (I did wonder, though, why Leigh and Miles ever needed to be on the set on the same day).

It could be argued, however, that Sir Alfred isn’t the the true title character of Hitchcock anyway. The film’s best element is Helen Mirren as Alma Reville Hitchcock. The good lady had been the director’s editor and screenwriter/script-doctor in the old days, and was still his most trusted adviser. In Mirren’s sharp, jumpy turn, she’s a clear-thinking, patient sort, but flustered and emotionally hungry from her husband’s neglect, and susceptible to the seductions of the screenwriter Whitfield Cook (Danny Huston).

Mirren’s vibrancy turns Hitchcock, at its best, into a mild comedy about a sexually frustrated middle-aged married couple; the fact that they were responsible for Psycho becomes a secondary matter. Yet Gervasi and McLaughlin do virtually claim for Alma an uncredited hand in the Psycho screenplay. While they go quite a bit farther with this suggestion than Rebello’s book does, there can be little doubt of how much he owed her (he was always fulsome in his praise of her). If the movie does nothing more than drag Alma’s role in the Hitchcock story out of her husband’s formidable shadow, it’s served a worthwhile purpose.

It’s a movie about the making of Sir Alfred’s 1960 classic Psycho, which is, truly, one of my two or three favorite movies. It has a fine cast, including a number of extremely attractive actresses, two of them—Scarlett Johansson and Jessica Biel—decked out in Psycho costumes. It’s set in an elegant recreation of Hollywood swank, circa the late ‘50s.

For all of these reasons, I enjoyed it. But I don’t know that even all of them together quite make it a good movie. Hitchcock, directed by Sacha Gervasi, from a script by John J. McLaughlin based on Stephen Rebello’s Alfred Hitchcock and the Making of Psycho, is fun to watch, but somehow I couldn’t quite find it convincing.

The main reason, I think, lies with the title personage. He’s played by Anthony Hopkins, padded and plastered to resemble the great man, to little avail. Powerhouse though Hopkins is, he couldn’t make me believe he was Alfred Hitchcock, or even simply forget he’s not Hitchcock, which might have been enough. It isn’t his fault—I don’t think any actor could. I haven’t seen the HBO movie The Girl, about the making of The Birds, but I hear Toby Jones doesn’t really swing it either.

The word “inimitable” is thrown around a lot in show business, but beyond the level of an easy Rich Little impression, Hitchcock really is inimitable, at least for someone of my generation. His canny on-camera self-promotion made him indelible to Boomer-era TV viewers and moviegoers. Nobody looks like that—for all the heroic efforts of the make-up folk, Hopkins looks more like late-vintage Rod Steiger than Hitchcock—nobody sounds like that, and nobody, I think, is really likely to capture that same grave drollery of manner. Hopkins gives a sometimes funny, sometimes touching portrait of a weird repressed middle-aged guy, but not of this particular weird repressed middle-aged guy.

Similarly, Hitchcock overplays its hand in dramatizing the making of Psycho. That film, as hardly anyone needs to be told, is Hitchcock’s modestly-budgeted, brilliantly-crafted California-gothic about Norman Bates, a sweet young motel manager who has an unusually close relationship with his mother—lethally close, to any strangers who encroach on it. It was adapted from a lurid little novel by Robert Bloch, which was in turn loosely based on the much grimmer real-life exploits of Wisconsin psychopath Ed Gein in 1957.

Hitchcock was slumming a bit when he took on the project, no doubt, challenging himself to make a profitable low-budget shocker, using the crew from his TV series, instead of the glamorous, romantic Technicolor thrillers he’d been turning out for the last decade or so. It’s doubtful he could have guessed he was making the movie for which he’d be best remembered.

Gervasi's film, on the other hand, tries to generate dramatic urgency by creating the sense that Psycho was a make-or-break crisis point in Hitchcock’s career. Much is made of Hitchcock’s own investment in the project, though the practical minded Mrs. H (Helen Mirren) points out that the peril to their fortune is along the lines of having to buy domestic rather than imported pate de fois gras. Gervasi and McLaughlin even resort to showing Hitchcock’s dreams haunted by the specter of Ed Gein (Michael Wincott). This feels like an overwrought reach.

So Hitchcock comes to life, mostly, in incidental episodes, and in the cast—James D’Arcy absolutely nailing the small role of Anthony Perkins, Toni Collette, ravishingly chic as Hitchcock’s right arm Peggy Robertson. Biel looks great as Vera Miles, and Johansson really did her homework as Janet Leigh, perfectly capturing Leigh’s pursed-lipped, mock-perplexed cock of the head (I did wonder, though, why Leigh and Miles ever needed to be on the set on the same day).

It could be argued, however, that Sir Alfred isn’t the the true title character of Hitchcock anyway. The film’s best element is Helen Mirren as Alma Reville Hitchcock. The good lady had been the director’s editor and screenwriter/script-doctor in the old days, and was still his most trusted adviser. In Mirren’s sharp, jumpy turn, she’s a clear-thinking, patient sort, but flustered and emotionally hungry from her husband’s neglect, and susceptible to the seductions of the screenwriter Whitfield Cook (Danny Huston).

Mirren’s vibrancy turns Hitchcock, at its best, into a mild comedy about a sexually frustrated middle-aged married couple; the fact that they were responsible for Psycho becomes a secondary matter. Yet Gervasi and McLaughlin do virtually claim for Alma an uncredited hand in the Psycho screenplay. While they go quite a bit farther with this suggestion than Rebello’s book does, there can be little doubt of how much he owed her (he was always fulsome in his praise of her). If the movie does nothing more than drag Alma’s role in the Hitchcock story out of her husband’s formidable shadow, it’s served a worthwhile purpose.

Thursday, November 22, 2012

HORNING IN

Happy Thanksgiving everybody!

In honor of that holiday…

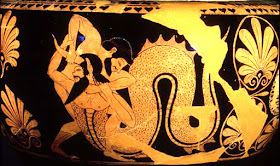

Monster-of-the-Week: …let’s turn to classical mythology for this week’s honoree, the river god Achelous, sometimes depicted as a sort of snake or fish monster, as in this pottery…

…or in Francois Joseph Bosio’s sculpture in the Louvre…

…and sometimes depicted as a giant bull, as in this mural by Thomas Hart Benton…

But what does Achelous have to do with Turkey Day, you may ask? Well, while scrapping with Hercules, Achelous got one of his horns ripped off, and, according to Ovid at least, said appendage became the Cornucopia, or Horn of Plenty. May it shower bounty upon us all.

In honor of that holiday…

Monster-of-the-Week: …let’s turn to classical mythology for this week’s honoree, the river god Achelous, sometimes depicted as a sort of snake or fish monster, as in this pottery…

…or in Francois Joseph Bosio’s sculpture in the Louvre…

Friday, November 16, 2012

ABE PLUS

It’s understandable if, after endless months of venomous, bitterly divisive politics, you aren’t particularly in the mood for a movie about a venomous, bitterly divisive period in American politics. But it would be a shame if political burnout kept audiences away from Lincoln, Steven Spielberg’s amazing movie built around the performance of Daniel Day-Lewis as the 16th President.

Honest Abe has been irresistible to moviemakers for more than a century, depicted sometimes reverently, as in D.W. Griffith’s Abraham Lincoln (1930), Young Mr. Lincoln (1939) or Abe Lincoln in Illinois (1940), and sometimes irreverently, as in Bill & Ted’s Excellent Adventure (1989) or this year’s Abraham Lincoln, Vampire Hunter. His achievements in office, his unassuming manner and his tragic end have, in the movies, generally resulted in one extreme or the other—either he’s a secular folk saint, or else he brings out the urge to spoof. There was TV miniseries called Lincoln back in the ‘80s, based on Gore Vidal’s book and with Sam Waterston as Abe, that made some effort to delve into the man’s psychology, but as I recall it was pretty slow going.

Spielberg’s film takes its time, too, and it’s pictorially beautiful. The cinematographer, Janusz Kaminski, infuses his compositions with a muted radiance that still seems realistic and immediate—the whole movie feels like a spring thaw. Yet it’s no iconic hagiography, and the unhurried pace that Spielberg sets gives the story a rising hum of dramatic energy. It’s not a tour of wax-museum tableaux from the man’s life. Surprisingly, and to the movie’s great benefit, it’s a story of nuts-and-bolts politics: the seemingly insoluble legislative wrangle to pass the 13th Amendment to the Constitution, ending slavery in the United States.

The script, by Tony Kushner, is partly adapted from Doris Kearns Goodwin’s 2005 book Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham Lincoln. The title suggests the difference in the new film’s approach. Political genius isn’t the first thing we associate with Lincoln. Yet the movie suggests that it was skill—at strategy, at marshalling favors and muzzling enemies, and at navigating the moral ambivalence of deep compromise—that, paradoxically, led him to accomplishments of moral grandeur.

Spielberg is at the top of his form here. I think film critics and buffs have, in a sense, underrated him for years. After his initial great success with Jaws and Close Encounters and E.T., he made some really terrible movies in the late ‘80s and early ‘90s—pushy, cloying, evasive stuff like Hook and Always—and many viewers naturally assumed that he was just going to be a sentiment-peddler forever. Some of them, I think, didn’t notice that Spielberg’s films in the ‘90s and early 2000s, though often highly uneven in terms of script or casting, were stunningly directed. Amistad and Munich and Saving Private Ryan and War of the Worlds were all flawed, but they were the often mesmerizing work of a master filmmaker—indeed, of a master filmmaker who had rediscovered and deepened his art.

We see this again in Lincoln, from the first images—of a horrifyingly bloody and brutal Civil War battle—to the first few lines of dialogue, as Lincoln converses with two black Union soldiers of very different temperament, and then with two awestruck white soldiers. There’s a weird and complex play of symmetry and conflicted agenda and formality and off-handedness, all presented with an effortlessness of revelation, that few other directors could have managed, or would even have thought to attempt.

What allows Spielberg to maintain this level of mastery through all that follows is the script. Kushner, who wrote the magnificent Angels in America plays, is one of the few contemporary dramatists who is both capable and unafraid of high-flown language, and the 19th Century idiom allows him to cut loose in this regard without sounding overly stylized.

Yet for all of Spielberg’s and Kushner’s brilliance, and for all the splendors of Kaminski’s camera, what makes Lincoln unique is Daniel Day-Lewis. Like the movie, his Lincoln will not suit all tastes, but for me, it’s one of the great performances in, maybe, the history of movies. It’s up there with Falconetti as Joan of Arc and Brando in The Godfather, and nobody but Day-Lewis could have given it.

A number of people I’ve talked to have been put off by the voice he uses—a thin, soft, upper-register drawl instead of a stentorian baritone. This is thought to be historically accurate, I believe, but it also works in the context of the character as Spielberg, Kushner and Day-Lewis conceive him. The movie operates on the premise that Lincoln was a compulsive raconteur. Again and again throughout the film, he stops, chuckles to himself, and launches a maddeningly digressive anecdote, and everyone in the room, even his friends and allies, look miserable as they sit there and wait for the punchline. This recurring gag, and the voice, connect to the idea that as a speaker Lincoln preferred quiet eloquence to thundering oratory, and as a leader preferred self-deprecating persuasion to conquest.

Day-Lewis doesn’t give the only fine performance in the film. Sally Field strikes the right strained yet sympathetic note as Mary Todd Lincoln; Joseph Gordon-Levitt is moving as Robert Lincoln, and Tommy Lee Jones lets it rip as Radical Republican abolitionist Thaddeus Stevens. Less flashy than Jones but just as essential to the movie is David Strathairn as Seward, and then there’s Bruce McGill as Stanton, and Jared Harris as Grant, and Jackie Earle Haley as Alexander Stephens and Gloria Reuben as Elizabeth Keckley and Hal Holbrook as Preston Blair and James Spader, John Hawkes and Tim Blake Nelson as three comically shady political operatives, among many other creditable turns.

Lincoln is, ultimately—and perhaps to its commercial peril—a movie of remarkable restraint. Spielberg, Kushner and Day-Lewis eschew almost every opportunity for melodrama. Even the score, by John Williams, keeps its voice down. Yet the cumulative effect of this low-key movie is, at least for one viewer, overwhelming.

Honest Abe has been irresistible to moviemakers for more than a century, depicted sometimes reverently, as in D.W. Griffith’s Abraham Lincoln (1930), Young Mr. Lincoln (1939) or Abe Lincoln in Illinois (1940), and sometimes irreverently, as in Bill & Ted’s Excellent Adventure (1989) or this year’s Abraham Lincoln, Vampire Hunter. His achievements in office, his unassuming manner and his tragic end have, in the movies, generally resulted in one extreme or the other—either he’s a secular folk saint, or else he brings out the urge to spoof. There was TV miniseries called Lincoln back in the ‘80s, based on Gore Vidal’s book and with Sam Waterston as Abe, that made some effort to delve into the man’s psychology, but as I recall it was pretty slow going.

Spielberg’s film takes its time, too, and it’s pictorially beautiful. The cinematographer, Janusz Kaminski, infuses his compositions with a muted radiance that still seems realistic and immediate—the whole movie feels like a spring thaw. Yet it’s no iconic hagiography, and the unhurried pace that Spielberg sets gives the story a rising hum of dramatic energy. It’s not a tour of wax-museum tableaux from the man’s life. Surprisingly, and to the movie’s great benefit, it’s a story of nuts-and-bolts politics: the seemingly insoluble legislative wrangle to pass the 13th Amendment to the Constitution, ending slavery in the United States.

The script, by Tony Kushner, is partly adapted from Doris Kearns Goodwin’s 2005 book Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham Lincoln. The title suggests the difference in the new film’s approach. Political genius isn’t the first thing we associate with Lincoln. Yet the movie suggests that it was skill—at strategy, at marshalling favors and muzzling enemies, and at navigating the moral ambivalence of deep compromise—that, paradoxically, led him to accomplishments of moral grandeur.

Spielberg is at the top of his form here. I think film critics and buffs have, in a sense, underrated him for years. After his initial great success with Jaws and Close Encounters and E.T., he made some really terrible movies in the late ‘80s and early ‘90s—pushy, cloying, evasive stuff like Hook and Always—and many viewers naturally assumed that he was just going to be a sentiment-peddler forever. Some of them, I think, didn’t notice that Spielberg’s films in the ‘90s and early 2000s, though often highly uneven in terms of script or casting, were stunningly directed. Amistad and Munich and Saving Private Ryan and War of the Worlds were all flawed, but they were the often mesmerizing work of a master filmmaker—indeed, of a master filmmaker who had rediscovered and deepened his art.