The Wife & I enjoyed tonight’s grand kitschy finale to two-plus weeks of pretty juicy Winter Games. It was most gratifying to see the great William Shatner, the glorious Catherine O’Hara & the valiant Michael J. Fox trotted out as the elder spokespersons for their country.

I honored Canada this weekend by watching Goin’ Down the Road, Don Shebib’s Canuck classic from 1970 about two rubes (Doug McGrath & Paul Bradley) from the Maritimes struggling to make it in Toronto…

Great stuff, with a painfully documentary feel, but it was hard to get the wonderful SCTV parody of it out of my head while watching it.

Keith Olbermann delivered one of his most affecting perorations this past week, about his father’s illness & how it relates to the vile “Death Panel” calumny. Check it out.

Sunday, February 28, 2010

Friday, February 26, 2010

GHOSTS

The disappearance of TV actor Andrew Koenig has had a sad resolution. As a boy, Koenig (the son of Walter Koenig, aka Mr. Chekhov) was the inspiration for Harlan Ellison’s heartbreaking 1977 short story “Jeffty Is Five,” which may be read here. Ellison wrote that his title character Jeffty “…in no small measure, is Josh [Andrew Koenig's real first name]: the sweetness of Josh, the intelligence of Josh, the questioning nature of Josh.”

Two movies opening here in the Valley this weekend:

The Crazies—The original 1973 The Crazies was not the finest hour in the noble career of director George A. Romero. It had only two elements that stick in my mind: First, the soldiers in the ghostly white HAZMAT suits…

…somehow scarier than the title threats, small-town Pennsylvanians turned into homicidal maniacs by a leaked biological weapon. Second was the little hippie chick (Lynn Lowry) with the angelic face who goes sweetly cuckoo.

Ms. Lowry turns up briefly in the current remake, as a nice lady riding by on a bike, singing “All Things Bright and Beautiful.” But the HAZMAT suits aren’t white this time, & while the new movie, reset in Iowa, is well-crafted & has a strong first half-hour, it falls apart after midpoint, collapsing into loose ends & unpleasant & oddly anticlimactic violence.

Still, there’s something resonant in the material—Barry Graham, who joined me for the screening Tuesday night, nailed it in this comment. Director Breck Eisner, early on, is adept at giving the Norman Rockwell milieu a sinister twist, as in the opening, set at a baseball game. There’s a nice black-comedy sequence involving an unbridled power saw and the crotch of the hero (Timothy Olyphant; in The Wife’s opinion any such threat would be tragic). There’s also a stunning, terrifying-yet-beautiful shot of a woman standing in front of a huge, roaring thresher in a darkened barn, silhouetted by the machine’s glaring lights. Moments like this suggest the movie that this could have been.

The Ghost Writer—Roman Polanski’s latest is this smooth, subtly funny thriller. In another sap-in-over-his-head part, Ewan McGregor plays the title character, a hack writer who specializes in ghosting celebrity autobiographies. He’s picked to transfuse some life into the numbing memoir of a Blair-like former Prime Minister, Adam Lang (Pierce Brosnan), who collaborated with the U.S. on the War on Terror.

Shortly after our hero arrives at the dull fellow’s isolated beach house on Martha’s Vineyard (the film was actually shot in Germany & on a Baltic island due to Polanski’s travel restrictions), Lang is embattled by war crimes charges in a rendition case, and The Ghost is besieged by protesters & other shady types along with the rest of Lang’s chilly circle. Eventually tension—partly sexual—arises between The Ghost & Lang’s smart, brittle wife (a stormy, amusing turn by Olivia Williams).

I found the degree of seriousness with which the rendition charges were taken by the media sadly unconvincing, but otherwise I found this low-key yarn, based on a novel by Robert Harris, thoroughly absorbing. There’s a fine baroque twist in the final minutes, & a good nasty joke in the final seconds. The actors are in good form, not just McGregor, Brosnan & Williams but also Kim Cattrall, Tom Wilkinson (especially excellent), Jim Belushi, Timothy Hutton & others. It was marvelous to see Eli Wallach in a one-scene role—he looks like he was around when the Old Testament was being written, but his timing & presence are still razor-sharp.

It’s possible that the source of the suspense in The Ghost Writer will be different for writers than for other viewers: At the beginning, The Ghost agrees to finish the job in a month. The more he got caught up in investigating the intrigue, the more I kept thinking “Dude, you better get back to the house & get your fingers on the fucking keyboard.”

Two movies opening here in the Valley this weekend:

The Crazies—The original 1973 The Crazies was not the finest hour in the noble career of director George A. Romero. It had only two elements that stick in my mind: First, the soldiers in the ghostly white HAZMAT suits…

…somehow scarier than the title threats, small-town Pennsylvanians turned into homicidal maniacs by a leaked biological weapon. Second was the little hippie chick (Lynn Lowry) with the angelic face who goes sweetly cuckoo.

Ms. Lowry turns up briefly in the current remake, as a nice lady riding by on a bike, singing “All Things Bright and Beautiful.” But the HAZMAT suits aren’t white this time, & while the new movie, reset in Iowa, is well-crafted & has a strong first half-hour, it falls apart after midpoint, collapsing into loose ends & unpleasant & oddly anticlimactic violence.

Still, there’s something resonant in the material—Barry Graham, who joined me for the screening Tuesday night, nailed it in this comment. Director Breck Eisner, early on, is adept at giving the Norman Rockwell milieu a sinister twist, as in the opening, set at a baseball game. There’s a nice black-comedy sequence involving an unbridled power saw and the crotch of the hero (Timothy Olyphant; in The Wife’s opinion any such threat would be tragic). There’s also a stunning, terrifying-yet-beautiful shot of a woman standing in front of a huge, roaring thresher in a darkened barn, silhouetted by the machine’s glaring lights. Moments like this suggest the movie that this could have been.

The Ghost Writer—Roman Polanski’s latest is this smooth, subtly funny thriller. In another sap-in-over-his-head part, Ewan McGregor plays the title character, a hack writer who specializes in ghosting celebrity autobiographies. He’s picked to transfuse some life into the numbing memoir of a Blair-like former Prime Minister, Adam Lang (Pierce Brosnan), who collaborated with the U.S. on the War on Terror.

Shortly after our hero arrives at the dull fellow’s isolated beach house on Martha’s Vineyard (the film was actually shot in Germany & on a Baltic island due to Polanski’s travel restrictions), Lang is embattled by war crimes charges in a rendition case, and The Ghost is besieged by protesters & other shady types along with the rest of Lang’s chilly circle. Eventually tension—partly sexual—arises between The Ghost & Lang’s smart, brittle wife (a stormy, amusing turn by Olivia Williams).

I found the degree of seriousness with which the rendition charges were taken by the media sadly unconvincing, but otherwise I found this low-key yarn, based on a novel by Robert Harris, thoroughly absorbing. There’s a fine baroque twist in the final minutes, & a good nasty joke in the final seconds. The actors are in good form, not just McGregor, Brosnan & Williams but also Kim Cattrall, Tom Wilkinson (especially excellent), Jim Belushi, Timothy Hutton & others. It was marvelous to see Eli Wallach in a one-scene role—he looks like he was around when the Old Testament was being written, but his timing & presence are still razor-sharp.

It’s possible that the source of the suspense in The Ghost Writer will be different for writers than for other viewers: At the beginning, The Ghost agrees to finish the job in a month. The more he got caught up in investigating the intrigue, the more I kept thinking “Dude, you better get back to the house & get your fingers on the fucking keyboard.”

Thursday, February 25, 2010

MOLAR POWER

Monster-of-the-Week: The 5-year-old son of a friend of mine recently had his first transaction with the Tooth Fairy, & found $5 under his pillow. Even adjusting for inflation, I think that’s a more generous rate than any of my teeth commanded back in the ‘60s & ‘70s.

Anyway, in honor of this auspicious occasion, & also as an incantation against him having any supernatural troubles down the road, this week let’s pay tribute to Matilda Dixon, the gruesome version of the Tooth Fairy found in the 2003 film Darkness Falls.

This is a rather ordinary piece of shocker moviemaking, but it begins with a wonderful, & seemingly whole-cloth fabricated, legendary backstory—Matilda’s the ghost of a kindly lady in the New England town of the title, who made a custom of giving local children gold coins for their baby teeth until she was hideously disfigured in a fire & then hanged when she was mistakenly suspected of a child murder.

Back from the dead, she’s a cowled, yowling hag in a porcelain facemask who swoops down from above to carry off kids who, having lost the last of their baby teeth (a nice touch of the phobia of incipient sexuality so essential to such tales), are unlucky enough to have caught sight of her. She can only get you, though, if you stray into the darkness—if you stay in the light, she can’t touch you. She cuts quite a memorable figure through this otherwise routine picture.

Here she is:

Here’s a more elegant design for her, regrettably unused in the film:

Anyway, in honor of this auspicious occasion, & also as an incantation against him having any supernatural troubles down the road, this week let’s pay tribute to Matilda Dixon, the gruesome version of the Tooth Fairy found in the 2003 film Darkness Falls.

This is a rather ordinary piece of shocker moviemaking, but it begins with a wonderful, & seemingly whole-cloth fabricated, legendary backstory—Matilda’s the ghost of a kindly lady in the New England town of the title, who made a custom of giving local children gold coins for their baby teeth until she was hideously disfigured in a fire & then hanged when she was mistakenly suspected of a child murder.

Back from the dead, she’s a cowled, yowling hag in a porcelain facemask who swoops down from above to carry off kids who, having lost the last of their baby teeth (a nice touch of the phobia of incipient sexuality so essential to such tales), are unlucky enough to have caught sight of her. She can only get you, though, if you stray into the darkness—if you stay in the light, she can’t touch you. She cuts quite a memorable figure through this otherwise routine picture.

Here she is:

Here’s a more elegant design for her, regrettably unused in the film:

Monday, February 22, 2010

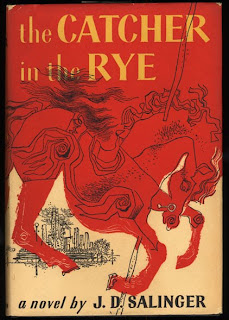

HOLDEN, MAURICE & ME; or, PUNCHER IN THE RYE

Like a lot of other people, I’ve been thinking a lot the last few weeks about J.D. Salinger, & especially about his most famous work, The Catcher in the Rye.

This, as you probably know, is the 1951 novel in which Holden Caulfield, a rich kid from Manhattan, flees the Pennsylvania prep school he’s flunked out of & heads to New York, but instead of going home spends a couple of days wandering the city, blowing money & alienating people.

I first read the book when I was in 10th grade, & again a couple of years later. I loved it, but looking back on it now, the identification that I felt with Holden, even though I shared it with millions of adolescents around the world, seems embarrassing to me. I don’t mean the kind of embarrassment one feels about some maudlin teenage poem or journal entry or yearbook inscription, nor do I mean that Catcher is a childish taste that I’ve outgrown—I do regard it as an authentic classic of American literature.

But thinking that Holden was “just like me” (or that I was just like him) seems now an overfamiliarity, an impertinence, almost an adolescent faux pas. It seems this way on two counts: social & emotional, & in both cases I’m grateful that it does.

To explain what I mean by “social,” I must indulge in autobiography: I grew up in a rural area on the other side of Pennsylvania from Holden’s prep school. I was the youngest of five kids. My Dad was a truck driver, & my Mom worked a variety of jobs to supplement his income—cashier in a book store, desk clerk in a motel, dishwasher in the cafeteria of the (public) high school I went to. Partly because of the hard work & resourcefulness of my parents, & partly because there were no seriously wealthy people in the area where I grew up—we lived next to railroad tracks, & the people who lived on The Other Side of the Tracks were no richer than we were—I never realized, as a kid, how broke we often were, & how much my parents struggled financially to provide for us.

For this reason, it never occurred to me when I read Catcher that Holden would have seen me as a poor kid, & probably wouldn’t have been comfortable with me. Indeed, thinking back on the book (I haven’t reread it) I recall Holden mentioning a roommate he had who owned shabby suitcases, & that while they liked each other, the difference in their status was an awkwardness for both of them. It never crossed my mind at the time that even this kid was probably from higher up the class ladder from me, & that in the unlikely event I ever even met Holden, it would be many times more awkward.

But the scene from Catcher that sticks most vividly in my mind all these years later is Holden’s tangle with Maurice, the pimp. After Holden’s abortive encounter with the prostitute, Maurice comes back to his room & shakes him down for five more dollars. Holden, enraged, taunts Maurice thusly (I found the passage online):

“You’re a dirty moron,” I said. “You’re a stupid chiseling moron, and in about two years you’ll be one of those scraggy guys that come up to you on the street and ask you for a dime for coffee. You’ll have snot all over your dirty overcoat, and you’ll be—”

At which point Maurice punches our hero in the stomach, knocking the wind out of him. Since the hooker has already appropriated the extra five bucks, it’s clear that Holden has touched a nerve, that Maurice punches him because he suspects his prophecy is probably accurate, & I can remember, as a teenager, enjoying Holden’s triumph.

It wasn’t until years later that it occurred to me that, socioeconomically speaking, I was ten times closer to Maurice than to Holden, & that even though I didn’t lead the life of a small-potatoes criminal it was still perfectly plausible that I could end up one of “those scraggy guys,” but that because of his class there was almost no chance that this could ever happen to Holden, no matter how he lived his life. Holden wants to catch the children before they fall off the cliff, but he doesn’t realize that he’s playing in the rye himself, & will be for the rest of his life, & that his class employs plenty of “catchers” already.

In light of this, the little snot’s prophecy somehow seemed a rather vicious response to Maurice’s pathetic chiseling. Maybe Holden (or Salinger) had a guilty pang over this as well, since at the very end of the book, when Holden is complaining that telling us his story has made him feel nostalgic for the people in it, he remarks “I think I even miss that goddam Maurice.” Well, I bet Maurice doesn’t freakin’ miss him.

The argument against all this, of course, is that class needn’t prevent identification with Holden any more than it does with, say, Hamlet (not that I’m placing the two works on the same level, of course), & that’s fair enough, on a literary level. My point here is only that I’ve walked around most of my life utterly oblivious to my class status, & in this, as I said, I regard myself as very fortunate. My parents raised me with no sense of class aspiration, & if I had actually met a kid like Holden, I probably would have just assumed that he & I could be friends, or if I had met one of the girls he dates I might have supposed that I could date her too.

Realizing that this was presumptuous of me would have been embarrassing, but aside from regret at missing out on the friendship or the date, I don’t think I would have felt any class bitterness over it. I’ve often wished I had more money, of course, but I don’t recall ever spending one second wishing that I was “high class” in the country club sense—both the obligations & amusements of that world have always seemed, from my outsider’s perspective, so tedious that I’ve always felt genuinely sorry for those who have to live in it.

Now we come to the second source of sheepishness I feel about my youthful enthusiasm for Catcher in the Rye. The novel is one of the key texts in the 20th-Century festishizing of the “young misfit.” But what makes Holden a misfit? He insists that he loathes “phonies,” while repeatedly “slinging the old bull” himself when he meets strangers, or tries to charm women, but this hardly makes him unusual among teens, nor are “phonies” really the source of the nervous breakdown toward which he’s heading.

When I read the book as a kid, the aspect of Holden’s character to which I paid the least attention—except possibly his social class—was his grief over the death of his brother Allie. What’s remarkable is how little Allie’s death figures in the commentaries I’ve read on the book (admittedly not many). This isn’t Salinger’s fault—Holden refers to Allie again & again throughout the story. One of the most moving scenes that I can recall comes when Holden, walking through the city, is overwhelmed by the feeling that he won’t make it across the streets, & mentally begs Allie to help him get across. It’s even more touching in light of the repressed, denial-oriented, stiff-upper-lip approach to bereavement that was typical, especially in Holden’s class, in the novel’s period.

But somehow all this mostly blipped past me as a teenage reader. I just thought, he’s a smart, screwed-up, special kid—like me! It never occurred to me that he was truly screwed-up, that he was acutely suffering, & for good reason. I was part of a couple of generations of teens who, thanks to Catcher & a few other cultural influences, thought that because we were bored & horny & impatient for adulthood to begin, that we were entitled—almost obligated—to be angst-ridden pains in the ass. But I had no loss in my life equivalent to Holden’s loss of Allie.

So that’s all I’m saying, I guess. For Catcher in the Rye to still be so firmly planted in my consciousness more than thirty years later, it must have been a vibrant work for me. I enjoyed Holden’s company, to a degree that I would probably never have gotten to in real-life. But, though no doubt I was an oddball kid in some ways, contrary to my earlier opinion, I was not Holden Caulfield, & neither, I’d guess, were most of the other teenage readers who thought they were. Thank God for that, too, meaning no goddam offense to Holden & all.

This, as you probably know, is the 1951 novel in which Holden Caulfield, a rich kid from Manhattan, flees the Pennsylvania prep school he’s flunked out of & heads to New York, but instead of going home spends a couple of days wandering the city, blowing money & alienating people.

I first read the book when I was in 10th grade, & again a couple of years later. I loved it, but looking back on it now, the identification that I felt with Holden, even though I shared it with millions of adolescents around the world, seems embarrassing to me. I don’t mean the kind of embarrassment one feels about some maudlin teenage poem or journal entry or yearbook inscription, nor do I mean that Catcher is a childish taste that I’ve outgrown—I do regard it as an authentic classic of American literature.

But thinking that Holden was “just like me” (or that I was just like him) seems now an overfamiliarity, an impertinence, almost an adolescent faux pas. It seems this way on two counts: social & emotional, & in both cases I’m grateful that it does.

To explain what I mean by “social,” I must indulge in autobiography: I grew up in a rural area on the other side of Pennsylvania from Holden’s prep school. I was the youngest of five kids. My Dad was a truck driver, & my Mom worked a variety of jobs to supplement his income—cashier in a book store, desk clerk in a motel, dishwasher in the cafeteria of the (public) high school I went to. Partly because of the hard work & resourcefulness of my parents, & partly because there were no seriously wealthy people in the area where I grew up—we lived next to railroad tracks, & the people who lived on The Other Side of the Tracks were no richer than we were—I never realized, as a kid, how broke we often were, & how much my parents struggled financially to provide for us.

For this reason, it never occurred to me when I read Catcher that Holden would have seen me as a poor kid, & probably wouldn’t have been comfortable with me. Indeed, thinking back on the book (I haven’t reread it) I recall Holden mentioning a roommate he had who owned shabby suitcases, & that while they liked each other, the difference in their status was an awkwardness for both of them. It never crossed my mind at the time that even this kid was probably from higher up the class ladder from me, & that in the unlikely event I ever even met Holden, it would be many times more awkward.

But the scene from Catcher that sticks most vividly in my mind all these years later is Holden’s tangle with Maurice, the pimp. After Holden’s abortive encounter with the prostitute, Maurice comes back to his room & shakes him down for five more dollars. Holden, enraged, taunts Maurice thusly (I found the passage online):

“You’re a dirty moron,” I said. “You’re a stupid chiseling moron, and in about two years you’ll be one of those scraggy guys that come up to you on the street and ask you for a dime for coffee. You’ll have snot all over your dirty overcoat, and you’ll be—”

At which point Maurice punches our hero in the stomach, knocking the wind out of him. Since the hooker has already appropriated the extra five bucks, it’s clear that Holden has touched a nerve, that Maurice punches him because he suspects his prophecy is probably accurate, & I can remember, as a teenager, enjoying Holden’s triumph.

It wasn’t until years later that it occurred to me that, socioeconomically speaking, I was ten times closer to Maurice than to Holden, & that even though I didn’t lead the life of a small-potatoes criminal it was still perfectly plausible that I could end up one of “those scraggy guys,” but that because of his class there was almost no chance that this could ever happen to Holden, no matter how he lived his life. Holden wants to catch the children before they fall off the cliff, but he doesn’t realize that he’s playing in the rye himself, & will be for the rest of his life, & that his class employs plenty of “catchers” already.

In light of this, the little snot’s prophecy somehow seemed a rather vicious response to Maurice’s pathetic chiseling. Maybe Holden (or Salinger) had a guilty pang over this as well, since at the very end of the book, when Holden is complaining that telling us his story has made him feel nostalgic for the people in it, he remarks “I think I even miss that goddam Maurice.” Well, I bet Maurice doesn’t freakin’ miss him.

The argument against all this, of course, is that class needn’t prevent identification with Holden any more than it does with, say, Hamlet (not that I’m placing the two works on the same level, of course), & that’s fair enough, on a literary level. My point here is only that I’ve walked around most of my life utterly oblivious to my class status, & in this, as I said, I regard myself as very fortunate. My parents raised me with no sense of class aspiration, & if I had actually met a kid like Holden, I probably would have just assumed that he & I could be friends, or if I had met one of the girls he dates I might have supposed that I could date her too.

Realizing that this was presumptuous of me would have been embarrassing, but aside from regret at missing out on the friendship or the date, I don’t think I would have felt any class bitterness over it. I’ve often wished I had more money, of course, but I don’t recall ever spending one second wishing that I was “high class” in the country club sense—both the obligations & amusements of that world have always seemed, from my outsider’s perspective, so tedious that I’ve always felt genuinely sorry for those who have to live in it.

Now we come to the second source of sheepishness I feel about my youthful enthusiasm for Catcher in the Rye. The novel is one of the key texts in the 20th-Century festishizing of the “young misfit.” But what makes Holden a misfit? He insists that he loathes “phonies,” while repeatedly “slinging the old bull” himself when he meets strangers, or tries to charm women, but this hardly makes him unusual among teens, nor are “phonies” really the source of the nervous breakdown toward which he’s heading.

When I read the book as a kid, the aspect of Holden’s character to which I paid the least attention—except possibly his social class—was his grief over the death of his brother Allie. What’s remarkable is how little Allie’s death figures in the commentaries I’ve read on the book (admittedly not many). This isn’t Salinger’s fault—Holden refers to Allie again & again throughout the story. One of the most moving scenes that I can recall comes when Holden, walking through the city, is overwhelmed by the feeling that he won’t make it across the streets, & mentally begs Allie to help him get across. It’s even more touching in light of the repressed, denial-oriented, stiff-upper-lip approach to bereavement that was typical, especially in Holden’s class, in the novel’s period.

But somehow all this mostly blipped past me as a teenage reader. I just thought, he’s a smart, screwed-up, special kid—like me! It never occurred to me that he was truly screwed-up, that he was acutely suffering, & for good reason. I was part of a couple of generations of teens who, thanks to Catcher & a few other cultural influences, thought that because we were bored & horny & impatient for adulthood to begin, that we were entitled—almost obligated—to be angst-ridden pains in the ass. But I had no loss in my life equivalent to Holden’s loss of Allie.

So that’s all I’m saying, I guess. For Catcher in the Rye to still be so firmly planted in my consciousness more than thirty years later, it must have been a vibrant work for me. I enjoyed Holden’s company, to a degree that I would probably never have gotten to in real-life. But, though no doubt I was an oddball kid in some ways, contrary to my earlier opinion, I was not Holden Caulfield, & neither, I’d guess, were most of the other teenage readers who thought they were. Thank God for that, too, meaning no goddam offense to Holden & all.

Sunday, February 21, 2010

DOG, FACE

Lily thought that the side of my head would be comfortable place to repose a while...

(photo credit: The Wife)

I don't know which is sadder: The fact that I was willing to keep my head in that position for a good ten minutes or so to accomodate her, or the amount of light that the top of my head picks up from the nearby lamp...

Here's another from this weekend of Lily:

(photo credit: Moi)

Also on the subject of dogs, & also of the Decline of Western Civilization: Mattel, perhaps inspired by the talking dog-collar in Up, is launching a dog-collar that sends you Tweets whenever your dog moves.

RIP to the delightful, ever-dotty Brit character actor Lionel Jeffries, who has passed on at 83; I confess I would have guessed that he was much older, &/or had died years ago.

(photo credit: The Wife)

I don't know which is sadder: The fact that I was willing to keep my head in that position for a good ten minutes or so to accomodate her, or the amount of light that the top of my head picks up from the nearby lamp...

Here's another from this weekend of Lily:

(photo credit: Moi)

Also on the subject of dogs, & also of the Decline of Western Civilization: Mattel, perhaps inspired by the talking dog-collar in Up, is launching a dog-collar that sends you Tweets whenever your dog moves.

RIP to the delightful, ever-dotty Brit character actor Lionel Jeffries, who has passed on at 83; I confess I would have guessed that he was much older, &/or had died years ago.

Friday, February 19, 2010

SHUTTER TO THINK

Martin Scorsese’s movies have often been filled with horrors, but before Shutter Island he had never made a horror movie, in the classic, gothic sense.

It’s a tantalizing prospect. Scorsese is one of the two or three best American directors of his generation, & he has made some authentic masterpieces. At its worst, admittedly, his style can be hyperactive & tiresome & showy; it can get between the viewer & the story the movie is telling. Such was the case with his closest previous flirtation with the horror genre, his feeble, overcooked remake of the great psychothriller Cape Fear.

But at its best, Scorsese’s style is unpredictable & explosive, & it can generate a bristling, hallucinatory atmosphere. His one-of-a-kind spin on the conventions of the scary movie could be a formidable experience. Or it could be laborious dud.

In the case of Shutter Island, it’s the former. Indeed, Scorsese’s so in control of the material here that it’s deceptive. He lays on the brushwork of old-school melodrama so floridly that we begin to lose confidence in him, to think that he’s painted himself into a corner, that he’s sacrificed a coherent plot for the sake of offering us a series of nightmare flourishes. Creepy flourishes they are, too, but I started to doubt that there was any way he’d be able to sort out & make sense of everything he’d thrown at us. Yet everything came together at the end, & with a real shock, too.

The setting is an asylum for the criminally insane on a fictitious Boston Harbor Island in 1954. Leonardo DiCaprio plays a Federal Marshal who arrives on a ferry to investigate the disappearance of an inmate. After being politely stonewalled by the top shrink (Ben Kingsley), the Marshal & his deferential partner (Mark Ruffalo) are trapped overnight by a wild storm. As he probes more deeply into the island’s secrets, he quickly comes to suspect that the smooth-talking doc & his staff are behind sinister, even monstrous mischief.

Based on Dennis Lehane’s 2003 novel, adapted by Laeta Kalogridis, it’s a standard set-up for a chiller, & within its framework Scorsese indulges in standard phobic gambits, from grinning, leering lunatics to clutching hands to heights to swarms of rats to an ominous old lighthouse. The cinematography, by the great Robert Richardson, imbues the film with a rich, unobtrusively stylized look of midcentury Technicolor, & I enjoyed watching Scorsese serve up one traditionally macabre sequence after another without parody, & with only a faint, strategic whisper of irony.

He serves up fine acting, too, not only from DiCaprio, who ultimately gives, I think, his best performance yet, but also from a knockout supporting cast. Kingsley & Ruffalo, Ted Levine as a baleful warden, Jackie Earle Haley as wretched inmate, John Carroll Lynch as an officious guard, Michelle Williams, Patricia Clarkson, & Emily Mortimer as various mystery women, & the disconcertingly unflappable Max Von Sydow as a senior shrink all strike just the right tone, but a special word should also be said for Robin Bartlett, who nails her quick little turn as a sensible inmate who once took an axe to her husband.

What makes Shutter Island more than a skillful genre exercise, though, is the final revelation of the case. Though the clues are deployed in a professional & reasonably cunning manner, it’s not that hard, in technical terms, to figure out the mystery at the heart of the investigation. In emotional terms, however, the secret proves truly, woundingly horrific, & in such an appallingly believable way that it’s almost like a reproach, exploding the fun of the tale’s gothic trappings with a burst of genuine tragedy. I didn’t see it coming, yet in retrospect I could see how carefully & subtly Scorsese & Kalogridis had prepared me for it.

The agony of the film’s climax & the eerie serenity of its final moments seem almost like Scorsese’s comment on the theatrics that came before. It’s as if he’s saying that such spookhouse thrills are a comparatively comforting shutter we use to close out the horrors of the real world.

RIP to the lovely MGM musical favorite Kathryn Grayson, who has passed on at 88…

It’s a tantalizing prospect. Scorsese is one of the two or three best American directors of his generation, & he has made some authentic masterpieces. At its worst, admittedly, his style can be hyperactive & tiresome & showy; it can get between the viewer & the story the movie is telling. Such was the case with his closest previous flirtation with the horror genre, his feeble, overcooked remake of the great psychothriller Cape Fear.

But at its best, Scorsese’s style is unpredictable & explosive, & it can generate a bristling, hallucinatory atmosphere. His one-of-a-kind spin on the conventions of the scary movie could be a formidable experience. Or it could be laborious dud.

In the case of Shutter Island, it’s the former. Indeed, Scorsese’s so in control of the material here that it’s deceptive. He lays on the brushwork of old-school melodrama so floridly that we begin to lose confidence in him, to think that he’s painted himself into a corner, that he’s sacrificed a coherent plot for the sake of offering us a series of nightmare flourishes. Creepy flourishes they are, too, but I started to doubt that there was any way he’d be able to sort out & make sense of everything he’d thrown at us. Yet everything came together at the end, & with a real shock, too.

The setting is an asylum for the criminally insane on a fictitious Boston Harbor Island in 1954. Leonardo DiCaprio plays a Federal Marshal who arrives on a ferry to investigate the disappearance of an inmate. After being politely stonewalled by the top shrink (Ben Kingsley), the Marshal & his deferential partner (Mark Ruffalo) are trapped overnight by a wild storm. As he probes more deeply into the island’s secrets, he quickly comes to suspect that the smooth-talking doc & his staff are behind sinister, even monstrous mischief.

Based on Dennis Lehane’s 2003 novel, adapted by Laeta Kalogridis, it’s a standard set-up for a chiller, & within its framework Scorsese indulges in standard phobic gambits, from grinning, leering lunatics to clutching hands to heights to swarms of rats to an ominous old lighthouse. The cinematography, by the great Robert Richardson, imbues the film with a rich, unobtrusively stylized look of midcentury Technicolor, & I enjoyed watching Scorsese serve up one traditionally macabre sequence after another without parody, & with only a faint, strategic whisper of irony.

He serves up fine acting, too, not only from DiCaprio, who ultimately gives, I think, his best performance yet, but also from a knockout supporting cast. Kingsley & Ruffalo, Ted Levine as a baleful warden, Jackie Earle Haley as wretched inmate, John Carroll Lynch as an officious guard, Michelle Williams, Patricia Clarkson, & Emily Mortimer as various mystery women, & the disconcertingly unflappable Max Von Sydow as a senior shrink all strike just the right tone, but a special word should also be said for Robin Bartlett, who nails her quick little turn as a sensible inmate who once took an axe to her husband.

What makes Shutter Island more than a skillful genre exercise, though, is the final revelation of the case. Though the clues are deployed in a professional & reasonably cunning manner, it’s not that hard, in technical terms, to figure out the mystery at the heart of the investigation. In emotional terms, however, the secret proves truly, woundingly horrific, & in such an appallingly believable way that it’s almost like a reproach, exploding the fun of the tale’s gothic trappings with a burst of genuine tragedy. I didn’t see it coming, yet in retrospect I could see how carefully & subtly Scorsese & Kalogridis had prepared me for it.

The agony of the film’s climax & the eerie serenity of its final moments seem almost like Scorsese’s comment on the theatrics that came before. It’s as if he’s saying that such spookhouse thrills are a comparatively comforting shutter we use to close out the horrors of the real world.

RIP to the lovely MGM musical favorite Kathryn Grayson, who has passed on at 88…

Thursday, February 18, 2010

THAT'S A PRETTY BIG EFF

Monster-of-the-Week: This week’s horrific honoree is more potty-mouthed than usual: The Monster in Fucking Frankenstein. You read it right, Fucking Frankenstein, a novel by Mary Wollstonecraft Shelley & “Mr. Matt Allen.” The latter scribe’s contribution consisted of adding the word “fucking,” or “fuck,” to the text of the iconic 1818 classic, more than a thousand times.

This is a real (albeit self-published) book. No kidding.

A sample:

“Oh fuck! No fucking mortal could support the horror of that countenance. A fucking mummy again imbued with animation could not be so hideous as this wretch. I had gazed on him while unfinished; he was ugly then; but when those muscles and joints were rendered capable of fucking motion, it became a thing such as even Dante could not have fucking conceived.

I passed the fucking night wretchedly…”

I didn’t want trees to die so that I could have a copy of Fucking Frankenstein, so I bought the Kindle edition. Irritating as I find this ridiculous stunt, having given it a read I must nonetheless acknowledge that it does demonstrate the enduring power both of the original Frankenstein, & also of the word “fuck.”

Implied in the choice of this particular novel for this treatment—as opposed to, say, Wuthering Fucking Heights—is the idea of revivification, of shocking life back into something dead. But Shelley’s Frankenstein most certainly does not need to be resuscitated. Despite the datedness of her gothic style & dilatory pace, despite the labored clumsiness of some of her plotting, Shelley’s prose hums with terrible & pitiless life. It certainly didn’t need everyone’s favorite scurrility to “help” it.

Yet somehow the word, in all its life-avowing intensity, seems very comfortable therein. It’s sort of like adding jalapenos to Havarti cheese: they aren’t needed, but they do add a certain zing.

It really is a wonderful word, when you think about it. The repetition of it here made me remember something that I once read attributed, I think, to Robert Graves—that in the British army, the word “fuck” was so ubiquitous that it had no meaning; it merely signaled the approach of a noun.

But…& I can’t believe I read the fucking thing closely enough to say this, but…I don’t think Allen did his job as well as he could have. Not to sound like an actor, but at times I felt like I could have done it better. I think I could have found more apt places to insert “fucking” into Frankenstein, & also simply more places. At times Allen seems like he’s being stingy—having set myself this absurd task, I would have been more generous with the fucking.

By the way, I pitched the idea of reviewing this book (using asterisks or brackets or something) to an editor at a daily for whom I’ve done many book columns. Normally an up-for-anything type of guy, he answered me thusly: “I gotta tell ya, Mark…No fucking way.”

This is a real (albeit self-published) book. No kidding.

A sample:

“Oh fuck! No fucking mortal could support the horror of that countenance. A fucking mummy again imbued with animation could not be so hideous as this wretch. I had gazed on him while unfinished; he was ugly then; but when those muscles and joints were rendered capable of fucking motion, it became a thing such as even Dante could not have fucking conceived.

I passed the fucking night wretchedly…”

I didn’t want trees to die so that I could have a copy of Fucking Frankenstein, so I bought the Kindle edition. Irritating as I find this ridiculous stunt, having given it a read I must nonetheless acknowledge that it does demonstrate the enduring power both of the original Frankenstein, & also of the word “fuck.”

Implied in the choice of this particular novel for this treatment—as opposed to, say, Wuthering Fucking Heights—is the idea of revivification, of shocking life back into something dead. But Shelley’s Frankenstein most certainly does not need to be resuscitated. Despite the datedness of her gothic style & dilatory pace, despite the labored clumsiness of some of her plotting, Shelley’s prose hums with terrible & pitiless life. It certainly didn’t need everyone’s favorite scurrility to “help” it.

Yet somehow the word, in all its life-avowing intensity, seems very comfortable therein. It’s sort of like adding jalapenos to Havarti cheese: they aren’t needed, but they do add a certain zing.

It really is a wonderful word, when you think about it. The repetition of it here made me remember something that I once read attributed, I think, to Robert Graves—that in the British army, the word “fuck” was so ubiquitous that it had no meaning; it merely signaled the approach of a noun.

But…& I can’t believe I read the fucking thing closely enough to say this, but…I don’t think Allen did his job as well as he could have. Not to sound like an actor, but at times I felt like I could have done it better. I think I could have found more apt places to insert “fucking” into Frankenstein, & also simply more places. At times Allen seems like he’s being stingy—having set myself this absurd task, I would have been more generous with the fucking.

By the way, I pitched the idea of reviewing this book (using asterisks or brackets or something) to an editor at a daily for whom I’ve done many book columns. Normally an up-for-anything type of guy, he answered me thusly: “I gotta tell ya, Mark…No fucking way.”

Tuesday, February 16, 2010

PERSIAN SHRUG

Happy Mardi Gras everybody!

Here’s the face that has at last launched my wish for John McCain to win an election...

A pal of mine studying for the LSAT sent me this rather splendid test question…

14. Some of the world's most beautiful cats are Persian cats. However, it must be acknowledged that all Persian cats are pompous, and pompous cats are invariably irritating.

If the statements above are true, each of the following must also be true EXCEPT:

A: Some of the world's most beautiful cats are irritating.

B: Some irritating cats are among the world's most beautiful cats.

C: Any cat that is not irritating is not a Persian cat.

D: Some pompous cats are among the world's most beautiful cats.

E: Some irritating and beautiful cats are not Persian cats.

(To what case law does this relate? Fluffy v. Fido Enterprises Ltd.?)

Anyway, as word problems have always been a nightmare for me, it wasn’t with much confidence that I guessed—but I got it right!

Any other takers?

Here’s the face that has at last launched my wish for John McCain to win an election...

A pal of mine studying for the LSAT sent me this rather splendid test question…

14. Some of the world's most beautiful cats are Persian cats. However, it must be acknowledged that all Persian cats are pompous, and pompous cats are invariably irritating.

If the statements above are true, each of the following must also be true EXCEPT:

A: Some of the world's most beautiful cats are irritating.

B: Some irritating cats are among the world's most beautiful cats.

C: Any cat that is not irritating is not a Persian cat.

D: Some pompous cats are among the world's most beautiful cats.

E: Some irritating and beautiful cats are not Persian cats.

(To what case law does this relate? Fluffy v. Fido Enterprises Ltd.?)

Anyway, as word problems have always been a nightmare for me, it wasn’t with much confidence that I guessed—but I got it right!

Any other takers?

Saturday, February 13, 2010

A BRONZE IN MEN’S SONNETEERING

The Winter Olympics, one of the few sporting events in which I take the slightest interest, kicked off last night in Vancouver with the usual kitschy pageantry—although it was pretty kick-ass to hear k.d. lang sing Leonard Cohen’s “Hallelujah.”

The Games proper commence today. The Wife is a Winter Games fanatic, & will likely be parked in front of the TV for many hours.

This was not the case in 2002, however—that year, I dragged her up to Salt Lake City to experience the Games live. She had often said that she’d always wanted to go, & I doubted that they’d ever be geographically closer to us. I managed to score tickets for exactly one event: Women’s Freestyle Skiing.

We had been out here in Arizona for more than a decade by that time, so long that we had forgotten how much winter can suck—we had to buy winter coats for the trip. But we remembered it fast as we hiked up the snowy mountain to the venue in Deer Valley, froze our asses off in the bleachers while we watched the lovely Australian Alisa Camplin sail to the Gold Medal...

...& then trudged our way back down to the shuttle buses.

That same day, on the sidewalk in front of the lodge, I saw Mitt Romney dancing to the music of a Dixieland band. This was the most Caucasian sight I ever expect to behold.

That night, back in our hotel in Salt Lake, while The exhausted Wife slept, I wrote this sonnet:

Though she despises snow, and might not wear,

To save her life, a pair of skates or skis,

She pulled a tasseled hat over her hair

And wrapped herself in vinyl and fake fleece.

Then, pluming silver steam out of her smile,

She rode on trains and buses, and her feet,

On shifting snow, that dizzy, final mile,

To take, at last, her own Olympic seat.

And shivering in authenticity,

She took her role as spectator with grace,

Subject, like the skiers, to gravity,

And likewise eager for her downhill race.

Four hours hence, back in her hotel bed,

She'd had it with Olympics--so she said.

The Games proper commence today. The Wife is a Winter Games fanatic, & will likely be parked in front of the TV for many hours.

This was not the case in 2002, however—that year, I dragged her up to Salt Lake City to experience the Games live. She had often said that she’d always wanted to go, & I doubted that they’d ever be geographically closer to us. I managed to score tickets for exactly one event: Women’s Freestyle Skiing.

We had been out here in Arizona for more than a decade by that time, so long that we had forgotten how much winter can suck—we had to buy winter coats for the trip. But we remembered it fast as we hiked up the snowy mountain to the venue in Deer Valley, froze our asses off in the bleachers while we watched the lovely Australian Alisa Camplin sail to the Gold Medal...

...& then trudged our way back down to the shuttle buses.

That same day, on the sidewalk in front of the lodge, I saw Mitt Romney dancing to the music of a Dixieland band. This was the most Caucasian sight I ever expect to behold.

That night, back in our hotel in Salt Lake, while The exhausted Wife slept, I wrote this sonnet:

Though she despises snow, and might not wear,

To save her life, a pair of skates or skis,

She pulled a tasseled hat over her hair

And wrapped herself in vinyl and fake fleece.

Then, pluming silver steam out of her smile,

She rode on trains and buses, and her feet,

On shifting snow, that dizzy, final mile,

To take, at last, her own Olympic seat.

And shivering in authenticity,

She took her role as spectator with grace,

Subject, like the skiers, to gravity,

And likewise eager for her downhill race.

Four hours hence, back in her hotel bed,

She'd had it with Olympics--so she said.

Friday, February 12, 2010

BENICIO DEL LOBO?

Two opening today:

The Wolfman—Benicio Del Toro is a talented fellow, & he’s said to be a fan of the classic monster pictures, which makes him my kind of dude. It pains me, therefore, to say that the new, big-budget version of 1941’s The Wolf Man, in which he plays the title role of the unhappy Lawrence Talbot, is pretty weak.

I had high hopes for this one—the original is one of the very best of the vintage monster classics—but my heart sank in the opening minutes, before the title had even appeared onscreen, with a sequence in which we’re shown way too much & scared way too little. The director, Joe Johnston, made the sweet October Sky & brought some panache to Jurassic Park III, but has otherwise mainly helmed impersonal action spectacles like Jumanji, & he seems to have zero feel for old-school spooky atmospherics. He tries to compensate with excessive gore—especially in a scene of the werewolf’s attack on a gypsy camp—but the severed limbs & splattered blood seem corny & fake. The film moves along, it isn’t boring, & I enjoyed the amusing long episode set in an asylum in London. But I can’t recall one moment of genuine dread or suspense.

Del Toro has a fine haunted look, & he brings an excellent physicality to the role—I loved his little canine head-shakes. But his line-readings are flat, as if he couldn’t quite figure out what to do with his voice, & he doesn’t have the hapless everyman quality that Lon Chaney, Jr. brought to the role in the original. On the upside, the other actors—Anthony Hopkins as Lawrence’s aloof father, Hugo Weaving as a Scotland Yard Inspector, Art Malik as the loyal Sikh manservant, Geraldine Chaplin as the fatalistic gypsy woman & especially Emily Blunt as the stricken fiancé of Lawrence’s slaughtered brother—are all solid.

Also on the upside, the production designs have an appealingly stylized look that might be called “Scooby Doo Gothic,” & though we’re shown far too much of it far too early, I loved Rick Baker’s makeup. His bushy-haired design has a wonderfully retro feel, like something from an EC horror comic. At times, indeed, Del Toro looked to me a little like Wolfman Jack.

One more very minor perplexity—The Wolf Man was set in Wales, while The Wolfman moves the action to England. Considering that Anthony Hopkins, perhaps the greatest living Welsh actor, is one of the stars, I wonder why?

The White Ribbon (Das Weisse Band)—Scarier by a long shot than The Wolfman is this Bergmanesque drama from the Austrian writer/director Michael Haneke. It’s set in a small German farming town the year before World War I begins, & it explores the lives of several families—the Baron and his wife, the widowed town doctor & his devoted midwife/mistress, a farm laborer whose wife has been killed in a mill accident, the stern local minister, & the gentle-souled but perceptive schoolteacher (Christian Friedel), who narrates from the perspective of old age, telling us at the beginning that the story may help to clarify some of what happened in his country over the past century.

Actually, the movie never even solidly clarifies what the frig happens in its own length, but it’s still riveting & chilling: In black & white images of bracing crispness, we’re shown a series of premeditated crimes, petty in spirit but viciously cruel in practice, aimed at the powerful & the powerless of the town alike. In a couple of cases, we see who the specific perpetrators are; in others we don’t, but it’s clear who, as a group, is behind these outrages. What we want to know is why—I was hoping for some great revelation of the specific motive, some elegant mystery-story snap to the resolution.

This is precisely what Haneke doesn’t give us, & though I think I would have found it a more satisfying movie if he had, I suppose it would also have been a lesser movie. Haneke wants us to grasp that the crimes are a generalized response to abuse—the physical, sexual, emotional & religious tyranny both suffered directly & observed by the children, who will, of course, be all grown up just in time to elect Hitler Chancellor.

What makes The White Ribbon most disturbing is that it isn’t pitiless. Haneke isn’t suggesting that the adults are intentionally villainous; it’s clear that, on the whole, they honestly think their repressive, stony-hearted values are the best approach to life. Nor are the kids presented gothically; they aren’t little demons out of a Charles Addams cartoon. On the contrary, they’re lovely, loving & likable.

Accepting his Golden Globe for the film, Haneke made a point of thanking the kids, & well he might have; they gave him fantastic performances. There’s a flawless scene in which the doctor’s little son quizzes his older sister about death, & when she gently & sweetly informs him that everyone, even the two of them, will have to die someday, his angelic little face sets in anger & he knocks his bowl to the floor. That’s pretty much how I’ve always felt about it.

The Wolfman—Benicio Del Toro is a talented fellow, & he’s said to be a fan of the classic monster pictures, which makes him my kind of dude. It pains me, therefore, to say that the new, big-budget version of 1941’s The Wolf Man, in which he plays the title role of the unhappy Lawrence Talbot, is pretty weak.

I had high hopes for this one—the original is one of the very best of the vintage monster classics—but my heart sank in the opening minutes, before the title had even appeared onscreen, with a sequence in which we’re shown way too much & scared way too little. The director, Joe Johnston, made the sweet October Sky & brought some panache to Jurassic Park III, but has otherwise mainly helmed impersonal action spectacles like Jumanji, & he seems to have zero feel for old-school spooky atmospherics. He tries to compensate with excessive gore—especially in a scene of the werewolf’s attack on a gypsy camp—but the severed limbs & splattered blood seem corny & fake. The film moves along, it isn’t boring, & I enjoyed the amusing long episode set in an asylum in London. But I can’t recall one moment of genuine dread or suspense.

Del Toro has a fine haunted look, & he brings an excellent physicality to the role—I loved his little canine head-shakes. But his line-readings are flat, as if he couldn’t quite figure out what to do with his voice, & he doesn’t have the hapless everyman quality that Lon Chaney, Jr. brought to the role in the original. On the upside, the other actors—Anthony Hopkins as Lawrence’s aloof father, Hugo Weaving as a Scotland Yard Inspector, Art Malik as the loyal Sikh manservant, Geraldine Chaplin as the fatalistic gypsy woman & especially Emily Blunt as the stricken fiancé of Lawrence’s slaughtered brother—are all solid.

Also on the upside, the production designs have an appealingly stylized look that might be called “Scooby Doo Gothic,” & though we’re shown far too much of it far too early, I loved Rick Baker’s makeup. His bushy-haired design has a wonderfully retro feel, like something from an EC horror comic. At times, indeed, Del Toro looked to me a little like Wolfman Jack.

One more very minor perplexity—The Wolf Man was set in Wales, while The Wolfman moves the action to England. Considering that Anthony Hopkins, perhaps the greatest living Welsh actor, is one of the stars, I wonder why?

The White Ribbon (Das Weisse Band)—Scarier by a long shot than The Wolfman is this Bergmanesque drama from the Austrian writer/director Michael Haneke. It’s set in a small German farming town the year before World War I begins, & it explores the lives of several families—the Baron and his wife, the widowed town doctor & his devoted midwife/mistress, a farm laborer whose wife has been killed in a mill accident, the stern local minister, & the gentle-souled but perceptive schoolteacher (Christian Friedel), who narrates from the perspective of old age, telling us at the beginning that the story may help to clarify some of what happened in his country over the past century.

Actually, the movie never even solidly clarifies what the frig happens in its own length, but it’s still riveting & chilling: In black & white images of bracing crispness, we’re shown a series of premeditated crimes, petty in spirit but viciously cruel in practice, aimed at the powerful & the powerless of the town alike. In a couple of cases, we see who the specific perpetrators are; in others we don’t, but it’s clear who, as a group, is behind these outrages. What we want to know is why—I was hoping for some great revelation of the specific motive, some elegant mystery-story snap to the resolution.

This is precisely what Haneke doesn’t give us, & though I think I would have found it a more satisfying movie if he had, I suppose it would also have been a lesser movie. Haneke wants us to grasp that the crimes are a generalized response to abuse—the physical, sexual, emotional & religious tyranny both suffered directly & observed by the children, who will, of course, be all grown up just in time to elect Hitler Chancellor.

What makes The White Ribbon most disturbing is that it isn’t pitiless. Haneke isn’t suggesting that the adults are intentionally villainous; it’s clear that, on the whole, they honestly think their repressive, stony-hearted values are the best approach to life. Nor are the kids presented gothically; they aren’t little demons out of a Charles Addams cartoon. On the contrary, they’re lovely, loving & likable.

Accepting his Golden Globe for the film, Haneke made a point of thanking the kids, & well he might have; they gave him fantastic performances. There’s a flawless scene in which the doctor’s little son quizzes his older sister about death, & when she gently & sweetly informs him that everyone, even the two of them, will have to die someday, his angelic little face sets in anger & he knocks his bowl to the floor. That’s pretty much how I’ve always felt about it.

Thursday, February 11, 2010

TEXAS, PARIS

RIP to Charlie Wilson, hard-partying Texas congressman & title character, played by Tom Hanks, of Charlie Wilson’s War, who has passed on at 76. Wilson was an ambiguous figure—his work to fund the Afghan resistance probably helped drive the Soviets out of Afghanistan & may have hastened the collapse of the Soviet bloc, but it probably also helped put the Taliban in power & make Afghanistan a home for al-Qaida.

Monster-of-the-Week: That’s right, it’s back! Everybody’s favorite feature from my old LiveJournal blog (OK, my favorite feature from my old LiveJournal blog), my weekly presentation of a memorable monster from the big or small screen, song or story, folklore, myth or comic book, will return until…well, until I get tired of doing it again.

This is because, with the new version of The Wolfman about to open—more about it tomorrow—I find werewolves much on my mind. From the Lon Chaney, Jr. original (which was The Wolf Man, not The Wolfman) to The Howling to An American Werewolf in London to Warren Zevon’s “Werewolves of London” to that great Barney Miller episode featuring Kenneth Tigar as Stephan Kopechne, matters lycanthropic have been my recent geeky preoccupation.

Accordingly I decided to read The Werewolf of Paris, by the American author & screenwriter Guy Endore. Though it wasn’t officially made into a movie until 1961’s Curse of the Werewolf—& that was a loose adaptation—Endore’s 1932 novel was highly influential on the genre.

The title character, & this week’s honoree, is the unfortunate Bertrand Caillet, a young man born under various maledictions. Conceived when a priest rapes a teenage girl, born on Christmas Day (once thought, according to this book, to be an evil portent) & saddled with a family curse besides, poor Bertrand grows up with hair on his palms, a unibrow & fanglike teeth. It comes as little surprise when, while serving as a soldier during the Paris Commune in 1871, he goes on a killing spree through the City of Light.

I started it expecting a fun piece of ‘30s-era pulp. I certainly didn’t expect what I got: A genuine work of literature that might even qualify as a neglected classic.

The book’s a bit of a marvel, really. Endore’s conceit is that we’re reading the popularization of a 19th-Century case study—& he generally keeps a poker face as to whether Bertrand’s condition is psychological or supernatural. This allows him to employ conventional narrative while retaining the authoritative tone of an epistolary work, like Stoker’s Dracula.

It also allows him to recount such lurid elements as murder, rape, incest, grave-robbing & cannibalism, as well as digressive satirical episodes & lengthy & by no means uninsightful discussions of science & superstition, rationalism & faith, conservatism & anarchism, all in a chatty prose, tinged with jaundiced irony toward all of the above. Yet there are passages of poignancy here as well, & true chills. I’m not sure why this seminal work isn’t acknowledged as belonging in the same league as Frankenstein, Dracula, Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde & The Phantom of the Opera.

The Werewolf of Paris appears to be out of print at the moment, though according to Amazon there’s a fancy new edition due in July, with an introduction by Thomas Tessier, author of the creepy, similarly ambiguous 1979 werewolf novel The Nightwalker. But the price, $59.85, seems slightly steep. I easily found an old paperback copy at a used bookstore for four bucks, but in the end I read the typo-riddled Kindle edition, for less than three bucks.

Monster-of-the-Week: That’s right, it’s back! Everybody’s favorite feature from my old LiveJournal blog (OK, my favorite feature from my old LiveJournal blog), my weekly presentation of a memorable monster from the big or small screen, song or story, folklore, myth or comic book, will return until…well, until I get tired of doing it again.

This is because, with the new version of The Wolfman about to open—more about it tomorrow—I find werewolves much on my mind. From the Lon Chaney, Jr. original (which was The Wolf Man, not The Wolfman) to The Howling to An American Werewolf in London to Warren Zevon’s “Werewolves of London” to that great Barney Miller episode featuring Kenneth Tigar as Stephan Kopechne, matters lycanthropic have been my recent geeky preoccupation.

Accordingly I decided to read The Werewolf of Paris, by the American author & screenwriter Guy Endore. Though it wasn’t officially made into a movie until 1961’s Curse of the Werewolf—& that was a loose adaptation—Endore’s 1932 novel was highly influential on the genre.

The title character, & this week’s honoree, is the unfortunate Bertrand Caillet, a young man born under various maledictions. Conceived when a priest rapes a teenage girl, born on Christmas Day (once thought, according to this book, to be an evil portent) & saddled with a family curse besides, poor Bertrand grows up with hair on his palms, a unibrow & fanglike teeth. It comes as little surprise when, while serving as a soldier during the Paris Commune in 1871, he goes on a killing spree through the City of Light.

I started it expecting a fun piece of ‘30s-era pulp. I certainly didn’t expect what I got: A genuine work of literature that might even qualify as a neglected classic.

The book’s a bit of a marvel, really. Endore’s conceit is that we’re reading the popularization of a 19th-Century case study—& he generally keeps a poker face as to whether Bertrand’s condition is psychological or supernatural. This allows him to employ conventional narrative while retaining the authoritative tone of an epistolary work, like Stoker’s Dracula.

It also allows him to recount such lurid elements as murder, rape, incest, grave-robbing & cannibalism, as well as digressive satirical episodes & lengthy & by no means uninsightful discussions of science & superstition, rationalism & faith, conservatism & anarchism, all in a chatty prose, tinged with jaundiced irony toward all of the above. Yet there are passages of poignancy here as well, & true chills. I’m not sure why this seminal work isn’t acknowledged as belonging in the same league as Frankenstein, Dracula, Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde & The Phantom of the Opera.

The Werewolf of Paris appears to be out of print at the moment, though according to Amazon there’s a fancy new edition due in July, with an introduction by Thomas Tessier, author of the creepy, similarly ambiguous 1979 werewolf novel The Nightwalker. But the price, $59.85, seems slightly steep. I easily found an old paperback copy at a used bookstore for four bucks, but in the end I read the typo-riddled Kindle edition, for less than three bucks.

Tuesday, February 9, 2010

HITTING THE WALLEYE

Odds & ends from a good Superbowl weekend:

Have you seen the new official portrait of the Supreme Court?

My pal Dave referred me to this awesome website, in which moviemakers comment on the trailers of their favorite movies. It’s addictive!

Breaking showbiz news: According to Variety, Taylor Lautner, the werewolf kid from the new Twilight flick, is slated to star in a movie version of Stretch Armstrong, the 70s-era toy. What’s next—GI Joe With Lifelike Hair: The Motion Picture?

My fellow Great Lakes-area Rust Belters may feel a nostalgic pang when I mention walleye or "yellow pike," that sublime freshwater delicacy...

If so, be advised: there’s a fast-food chain out of Wisconsin called Culver’s that has opened a couple of locations here in the Valley, including one quite near my place at Metro Center. Culver’s is offering walleye, for a limited time only. Get thee down there & enjoy; you may well see me leaving with a large carry-out bag.

Have you seen the new official portrait of the Supreme Court?

My pal Dave referred me to this awesome website, in which moviemakers comment on the trailers of their favorite movies. It’s addictive!

Breaking showbiz news: According to Variety, Taylor Lautner, the werewolf kid from the new Twilight flick, is slated to star in a movie version of Stretch Armstrong, the 70s-era toy. What’s next—GI Joe With Lifelike Hair: The Motion Picture?

My fellow Great Lakes-area Rust Belters may feel a nostalgic pang when I mention walleye or "yellow pike," that sublime freshwater delicacy...

If so, be advised: there’s a fast-food chain out of Wisconsin called Culver’s that has opened a couple of locations here in the Valley, including one quite near my place at Metro Center. Culver’s is offering walleye, for a limited time only. Get thee down there & enjoy; you may well see me leaving with a large carry-out bag.

Friday, February 5, 2010

TOLSTOYS IN THE ANTIC

Recently I reread one of my favorite essays, George Orwell’s “Lear, Tolstoy and the Fool” (1947). Focusing on Tolstoy’s own essay, written in the early 1900s, about his lifelong dislike of Shakespeare’s work & his bafflement at the Bard’s fine reputation, Orwell draws a convincing parallel between Shakespeare’s Lear & the elderly Tolstoy.

I thought of this essay again while watching The Last Station, a tragicomedy about the chaotic final year in the life of the Russian master, played by Christopher Plummer, paired in a heavyweight title bout with Helen Mirren as Sophia Andreyevna, the Countess Tolstoy.

This highly civilized entertainment, opening today in the Valley, was written & directed by Michael Hoffman. Ironically, Hoffman has already brought Shakespeare to the screen with his fine 1999 A Midsummer Night’s Dream, & is also the fellow behind the underappreciated 1991 farce Soapdish. He’s long been on the underappreciated side in general, I think.

Tolstoy’s last days offer one of the most spectacular illustrations ever of the maxim that there’s no fool like an old fool, & also of the less widely grasped truth that a fool & a great genius can reside in the same person. Toward the end of his life Tolstoy, revered worldwide but especially throughout Russia, founded a sort of ecumenical social movement/religious sect based on unconditional love of humanity, pacifism, detachment from private property, & celibacy.

Since he was a Count with a beautiful country estate, & wealthy anyway because of his books, this was a significant renunciation for him. & since he was married to a beautiful woman of histrionic temperament who was still passionately in love with him & still very accustomed to the life of an aristocrat (& who had given him thirteen children!), his spiritual awakening did not, to put it mildly, go over well at home.

The movie dramatizes these scenes of domestic war, & not much peace, through the eyes of Valentin Bulgakov (James McAvoy), an ardent young “Tolstoyan” who is pressed into service as Tolstoy’s new personal secretary. He’s also asked to serve as a spy for Vladimir Chertkov, the boss Tolstoyan & Sophia Andreyevna’s loathed rival for her husband’s devotion (& his inheritance), played with seething unctuousness by Paul Giamatti.

What ensues is a series of episodes, mostly comic though with an increasingly poignant edge, of the collapse of Tolstoy’s marriage, his peace & his health, all played out against a bucolic backdrop. Eventually he & a few of his followers, including his daughter, leave home, with no real destination in mind, & he is left bedridden in the remote train station of the title.

Hoffman’s direction & script (adapted from a novel by Jay Parini), suggest that he sides, on the whole, with Sophia Andreyevna’s view, & regards the Tolstoyans as sycophants, buffoons, & possibly even con artists, & Tolstoy as their vain & gullible mark. Yet he doesn’t deny Sophia Andreyevna’s snobbery & patrician bigotry, her narcissism & penchant for soap-opera-ish melodrama. Nor does he deny the courage & greatness of heart that led Tolstoy to these ruinous valedictory gestures.

Most importantly, Hoffman gets delightful performances from his cast. McAvoy has a lovely moment where he bursts into tears after his idol expresses interest in his work. Kerry Condon is mischievously sexy as a young Tolstoyan woman who tempts him from the true path, & Anne-Marie Duff is forbidding as Sasha Tolstoy. Mirren lets it rip as the Countess, rolling her eyes at her husband’s folly one minute, wailing like Sarah Bernhardt the next.

In the end, though, the movie belongs to Plummer, who makes Tolstoy a magnificent yet lovable sap, with all sorts of mutterings & chuckles rumbling out from behind his long white beard. It might displease Tolstoy, but somebody really ought to let Plummer play Lear sometime soon.

I thought of this essay again while watching The Last Station, a tragicomedy about the chaotic final year in the life of the Russian master, played by Christopher Plummer, paired in a heavyweight title bout with Helen Mirren as Sophia Andreyevna, the Countess Tolstoy.

This highly civilized entertainment, opening today in the Valley, was written & directed by Michael Hoffman. Ironically, Hoffman has already brought Shakespeare to the screen with his fine 1999 A Midsummer Night’s Dream, & is also the fellow behind the underappreciated 1991 farce Soapdish. He’s long been on the underappreciated side in general, I think.

Tolstoy’s last days offer one of the most spectacular illustrations ever of the maxim that there’s no fool like an old fool, & also of the less widely grasped truth that a fool & a great genius can reside in the same person. Toward the end of his life Tolstoy, revered worldwide but especially throughout Russia, founded a sort of ecumenical social movement/religious sect based on unconditional love of humanity, pacifism, detachment from private property, & celibacy.

Since he was a Count with a beautiful country estate, & wealthy anyway because of his books, this was a significant renunciation for him. & since he was married to a beautiful woman of histrionic temperament who was still passionately in love with him & still very accustomed to the life of an aristocrat (& who had given him thirteen children!), his spiritual awakening did not, to put it mildly, go over well at home.

The movie dramatizes these scenes of domestic war, & not much peace, through the eyes of Valentin Bulgakov (James McAvoy), an ardent young “Tolstoyan” who is pressed into service as Tolstoy’s new personal secretary. He’s also asked to serve as a spy for Vladimir Chertkov, the boss Tolstoyan & Sophia Andreyevna’s loathed rival for her husband’s devotion (& his inheritance), played with seething unctuousness by Paul Giamatti.

What ensues is a series of episodes, mostly comic though with an increasingly poignant edge, of the collapse of Tolstoy’s marriage, his peace & his health, all played out against a bucolic backdrop. Eventually he & a few of his followers, including his daughter, leave home, with no real destination in mind, & he is left bedridden in the remote train station of the title.

Hoffman’s direction & script (adapted from a novel by Jay Parini), suggest that he sides, on the whole, with Sophia Andreyevna’s view, & regards the Tolstoyans as sycophants, buffoons, & possibly even con artists, & Tolstoy as their vain & gullible mark. Yet he doesn’t deny Sophia Andreyevna’s snobbery & patrician bigotry, her narcissism & penchant for soap-opera-ish melodrama. Nor does he deny the courage & greatness of heart that led Tolstoy to these ruinous valedictory gestures.

Most importantly, Hoffman gets delightful performances from his cast. McAvoy has a lovely moment where he bursts into tears after his idol expresses interest in his work. Kerry Condon is mischievously sexy as a young Tolstoyan woman who tempts him from the true path, & Anne-Marie Duff is forbidding as Sasha Tolstoy. Mirren lets it rip as the Countess, rolling her eyes at her husband’s folly one minute, wailing like Sarah Bernhardt the next.

In the end, though, the movie belongs to Plummer, who makes Tolstoy a magnificent yet lovable sap, with all sorts of mutterings & chuckles rumbling out from behind his long white beard. It might displease Tolstoy, but somebody really ought to let Plummer play Lear sometime soon.

Wednesday, February 3, 2010

NO GUTS, NO GLORY

A couple of weeks late for stateside Burns Suppers on January 25, haggis is once again legal in the U.S. My Mom cooked one for my high school graduation.

I'm proud to say that I can recite the traditional blessing of the dish, Burns' "To A Haggis," from memory. If anyone's whipping one up next January, I'm available...

I'm proud to say that I can recite the traditional blessing of the dish, Burns' "To A Haggis," from memory. If anyone's whipping one up next January, I'm available...

Tuesday, February 2, 2010

NAMING NOMS

Hope everyone had a great Groundhog Day.

My Mom always pointed out that, living in Erie, having only six more weeks of winter was reason enough to celebrate.

In Phoenix, of course, we root for Phil to see his shadow.

This year’s Oscar nominations were announced this morning. Three remarks on this:

First, great though Christopher Plummer was in The Last Station, I still hope that Christoph Waltz wins for Inglourious Basterds.

Second, though I think, on the whole, that the new policy of ten Best Picture nominees rather than five is a bad idea, I can’t help but be pleased that it’s afforded a nomination to District 9, which for imaginative use of the sci-fi-parable form makes Avatar look like an airbrush painting on the side of a stoner’s van.

Finally, give it up for The Wife! She wrote down her predictions last night, & she missed on only three counts—guessing that Peter Sarsgaard (for An Education) & Christian McKay (for Me & Orson Welles) would get Best Supporting Actor nods, & that Marion Cotillard rather than Penelope Cruz would get the nod for Nine. Otherwise she was spot-on, across the board. I should take her to Vegas & put money on her picks for the winners.

My Mom always pointed out that, living in Erie, having only six more weeks of winter was reason enough to celebrate.

In Phoenix, of course, we root for Phil to see his shadow.

This year’s Oscar nominations were announced this morning. Three remarks on this:

First, great though Christopher Plummer was in The Last Station, I still hope that Christoph Waltz wins for Inglourious Basterds.

Second, though I think, on the whole, that the new policy of ten Best Picture nominees rather than five is a bad idea, I can’t help but be pleased that it’s afforded a nomination to District 9, which for imaginative use of the sci-fi-parable form makes Avatar look like an airbrush painting on the side of a stoner’s van.

Finally, give it up for The Wife! She wrote down her predictions last night, & she missed on only three counts—guessing that Peter Sarsgaard (for An Education) & Christian McKay (for Me & Orson Welles) would get Best Supporting Actor nods, & that Marion Cotillard rather than Penelope Cruz would get the nod for Nine. Otherwise she was spot-on, across the board. I should take her to Vegas & put money on her picks for the winners.